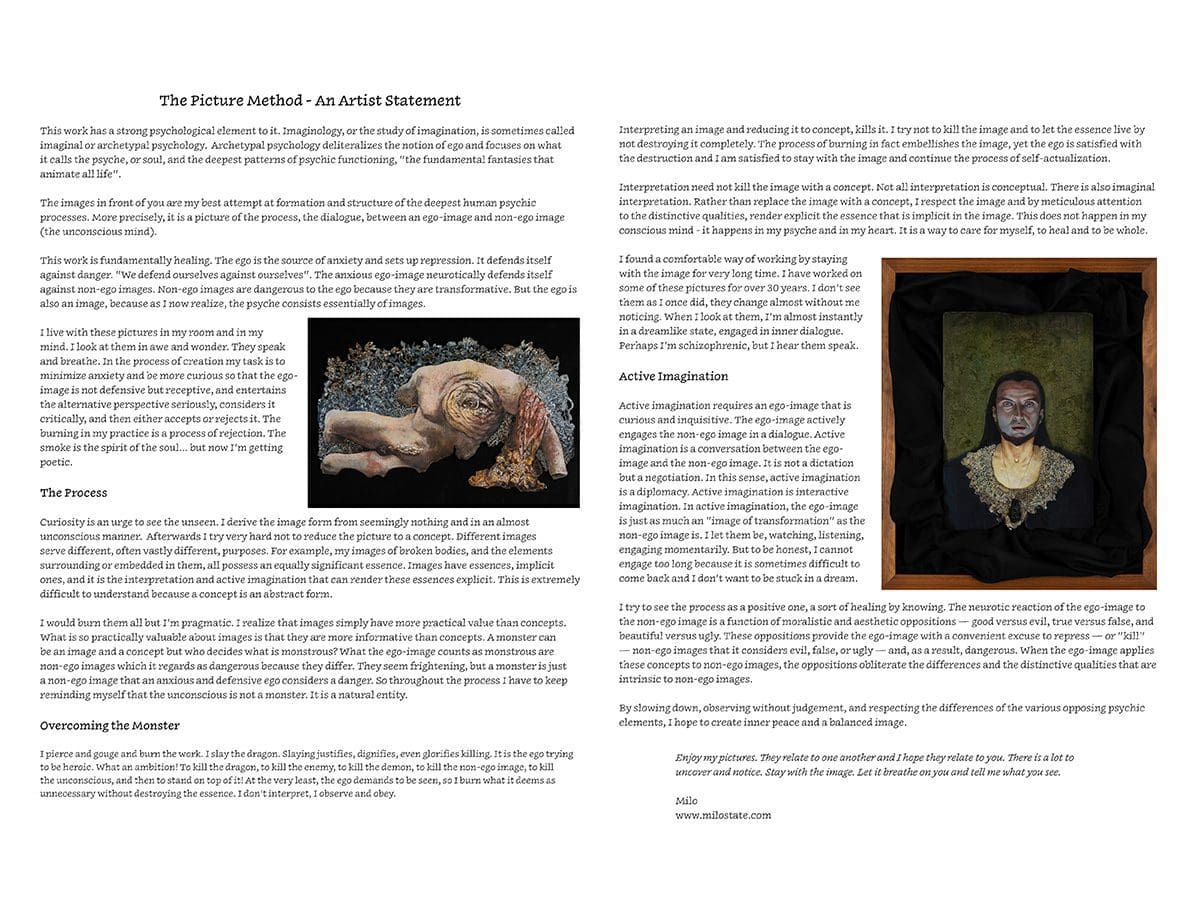

The Picture Method exhibition is an exploration of the human psyche through the lens of Imaginology, an intricate study of the human imagination often paralleled with archetypal psychology. This exhibition delves deep into the realm of the unconscious, navigating the waters of our mental processes, and challenging our comprehension of self and reality.

Imaginology, as a discipline, focuses on the psyche or the soul, probing into the deepest patterns of psychic functioning. It espouses the fundamental fantasies that animate all life, giving rise to a vibrant tapestry of human experience. In this exhibition, you’ll encounter my interpretation of these fantasies, crystallized into visual representations, each attempting to map the complex terrain of the human mind.

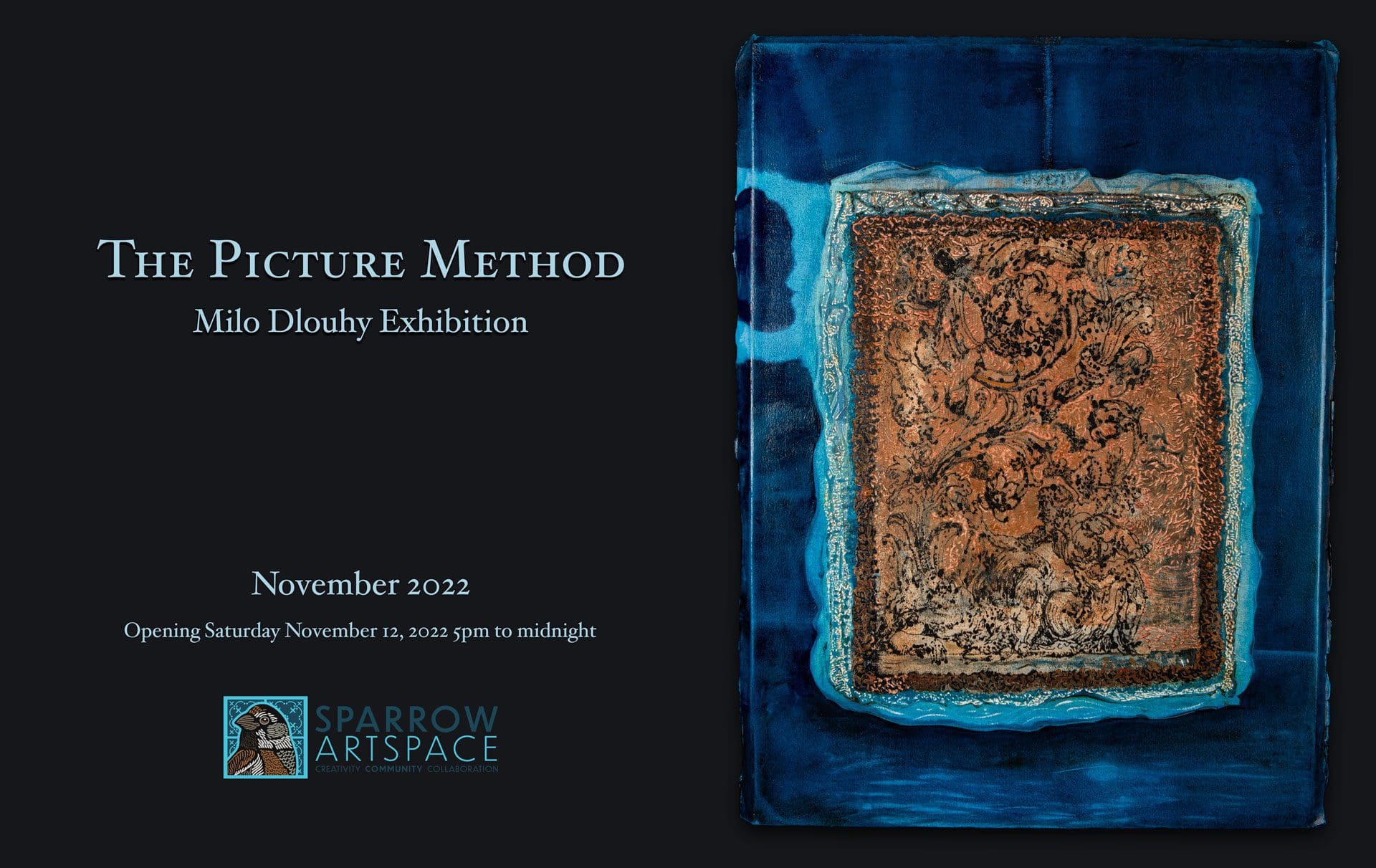

The images on display are the results of my exploration and understanding of the deepest human psychic processes. They represent a dialogue between ego-image and non-ego image, capturing the continuous conversation between the conscious and the unconscious realms of the mind. In essence, these images are visual representations of the psychological dance between self-awareness and the unknown, offering a glimpse into a world usually hidden from conscious view.

My work is not just an artistic endeavour, but also a healing process. The ego, as a defender of the self, is a primary source of anxiety and repression. This defensive mechanism often sets up barriers against elements perceived as threatening or transformative. As these images suggest, the ego itself is just an image, a construct that exists within the vast cosmos of the psyche. The images on display here are my companions, my constant reminders of this profound realization.

Through the process of creation, I strive to reduce anxiety and foster curiosity, cultivating a receptive rather than defensive ego-image. This approach encourages an open dialogue with the non-ego images, considering them critically, accepting or rejecting them based on a deeper understanding rather than fear. The act of burning in my practice symbolizes rejection, and the smoke, a poetic embodiment of the soul’s spirit.

Intriguingly, curiosity propels my process, leading me to unseen territories of the mind. The images that emerge from this exploration are drawn from the nebulous ether of the unconscious. Each image serves a unique purpose, embodying an essence that is often implicit, waiting for interpretation and active imagination to render it explicit.

Images of broken bodies, and the elements surrounding or embedded in them, hold a particular significance in my work. They convey the inherent vulnerability of the human condition, depicting the fragility and resilience of our physical and emotional selves. The challenge lies in resisting the temptation to reduce these images to mere concepts, as the essence of an image transcends the limitations of abstract thought.

To see a monster as merely a concept is to overlook its potential as a transformative image. To the anxious and defensive ego, a monster is merely a non-ego image that poses a perceived threat. Yet, a monster could also represent the unknown, the transformative potential of the unconscious mind. Therefore, in my work, I strive to view the unconscious not as a monstrous entity, but as a natural, integral part of the human psyche.

In the end, while the temptation to burn these images out of pragmatism exists, I recognize their inherent value. Images are repositories of information, far more informative than abstract concepts. They represent the richness of human experience, offering insights into our collective and individual psyches.

Through The Picture Method, I invite you to embark on a journey into the depths of your own psyche, to confront and embrace the images that dwell there, and to witness the transformative potential of your own imagination.

Confronting the Beast Within

In this work, I engage directly with the depths of the unconscious, often resorting to drastic measures to make sense of the unknown. I puncture, incise, and even incinerate my creations in a symbolic act of slaying the metaphorical dragon—the unknown and frightening aspects of the unconscious. This act of conquest, of standing victorious atop the vanquished foe, echoes the ego’s desire for heroism, its yearning for recognition and validation.

Yet, in this violent ritual, I aim not to obliterate but to refine, to pare down the unnecessary without annihilating the essence. Rather than interpreting or imposing my conscious will, I choose to observe and obey, acting as a witness to the unfolding narrative of the unconscious.

Interpretation, especially when it seeks to reduce the rich tapestry of an image to a mere concept, can often lead to the death of that image. My endeavour is to preserve the vitality of the image, allowing its essence to endure. The act of burning, paradoxically, enhances the image, satisfying the ego’s need for destruction while allowing me to persist in my journey of self-actualization.

Interpretation need not always be a conceptual slaughter of the image. There exists an alternative—an imaginal interpretation. In this approach, I honour the image, attentively uncovering the essence that subtly infuses it. This is not an intellectual exercise but an intuitive process, happening not in my conscious mind but in the depths of my psyche, in the sanctuary of my heart. It is an act of self-care, a step towards healing and wholeness.

Over the years, I have found solace in the patient contemplation of my work. Some images have evolved alongside me for over three decades, their metamorphosis so gradual it escapes my conscious notice. When I gaze upon them, I am transported into a dreamlike realm, immersed in an introspective dialogue. Though this state may seem akin to schizophrenia, it is a meaningful conversation with the depths of my being.

The Dance of Active Imagination

Active imagination necessitates an ego that is curious and investigative. This approach fosters a dialogue between the ego-image and the non-ego image, a negotiation rather than a dictation. Active imagination, in essence, is a diplomatic exchange, an interactive dance between different facets of the self. In this dance, both the ego-image and the non-ego image act as catalysts of transformation.

Yet, while I observe, listen, and momentarily engage with these images, I remain cautious not to delve too deep, wary of the challenge in disentangling myself from this dreamlike state.

My endeavour is to approach this process positively, viewing it as a form of healing through self-awareness. The ego-image often reacts neurotically to non-ego images due to moralistic and aesthetic dichotomies—good against evil, truth against falsehood, beauty against ugliness. These oppositions provide the ego-image an excuse to repress, or “kill,” non-ego images that it perceives as evil, false, or ugly, and thus, threatening. When applied, these concepts obliterate the unique qualities intrinsic to non-ego images.

By slowing down, observing without judgement, and honouring the distinctions among the various psychic elements, I aspire to create a balanced representation. This careful navigation of the psychic landscape is my attempt to reconcile these oppositions, ultimately leading to a more nuanced understanding of my unconscious.

ABOUT ACTIVE IMAGINATION

Active imagination, a term coined by Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung, is a profound and complex method of exploration and dialogue with the unconscious mind. This practice, as a part of Jung’s analytical psychology, bridges the gap between the conscious and unconscious realms, facilitating personal growth and self-understanding.

Concept of Active Imagination

The concept of active imagination arises from the recognition that the unconscious mind is an active, contributing, and essential part of our psychological life. The unconscious contains images, narratives, and entities that are often translated into dreams, fantasies, and impulses in our waking life. Unlike passive daydreaming, active imagination is a deliberate, conscious endeavor where one consciously engages with the contents of the unconscious.

The Process of Active Imagination

The process of active imagination begins with a state of receptivity in which one allows images to rise spontaneously from the unconscious. This state may be facilitated by focusing on a specific dream symbol, an emotion, or an inner image that has been particularly significant or persistent. The objective is to let these images or narratives unfold themselves without conscious intervention.

Once an image or narrative surfaces, the individual consciously interacts with it. This interaction can involve questioning the image, challenging it, or allowing it to evolve on its own terms. It’s a kind of intrapsychic dialogue in which the conscious mind interacts with the unconscious on an equal footing.

Active imagination can manifest through various channels, including visualization, automatic writing, or artistic activities. The form it takes can be deeply personal, depending on one’s natural inclinations and talents.

The Role of Active Imagination in Personal Growth

Active imagination plays a crucial role in personal growth by fostering a constructive dialogue with the unconscious. The unconscious, according to Jung, is not merely a repository of repressed memories and primitive instincts. It is a dynamic realm that contains a wealth of wisdom, creativity, and insight that can guide and enrich our conscious life.

By engaging with the unconscious through active imagination, we can uncover hidden aspects of ourselves, resolve internal conflicts, and integrate disparate parts of our psyche. This process can lead to a state of individuation, a term used by Jung to describe the journey towards wholeness and self-realization.

The Importance of Active Imagination in Therapy

In therapy, active imagination serves as a powerful tool for accessing and working with unconscious material. It provides a space where dream images or symbols can be further explored and understood. This technique allows the therapist and client to work together to uncover the deeper meanings of these symbols, leading to insights and resolutions that might not be accessible through conscious cognition alone.

Cautions and Considerations

While active imagination can be a potent tool for self-exploration, it is not without its risks. Delving into the unconscious can reveal unsettling or disturbing content. This exploration can lead to intense emotions or even a temporary state of disorientation. Therefore, active imagination should be practiced with care, preferably under the guidance of a trained analyst or therapist, especially in the beginning.

REFERENCES

References

Adams, M.V. (2001) The Mythological Unconscious, New York and London: Karnac.

Adams, M.V. (2004) The Fantasy Principle: Psychoanalysis of the Imagination, Hove and New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Allen, J., and Griffiths, J. (1979) The Book of the Dragon, Secaucus, NJ: Chartwell Books.

Atherton, C. (1998) “Introduction,” in C. Atherton (ed.), Monsters and Monstrosity in Greek and Roman Culture, Bari: Levante Editori, pp. vii-xxxiv.

Bateson, G. (1987) Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology, Northvale, NJ, and London: Jason Aronson.

Bateson, G. (1991) Sacred Unity: Further Steps to an Ecology of Mind, ed. R.E. Donaldson, New York: HarperCollins.

Booker, C. (2004) The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories, London and New York: Continuum.

Campbell, J. (1968) The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

De Voragine, J. (1991) The Golden Legend, trans. G. Ryan and H. Ripperger, Salem, NH: Ayer.

Derrida, J. (1973) “Differance,” in Speech and Phenomena: And Other Essays on Husserl’s Theory of Signs, trans. D.B. Allison and N. Garver, Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, pp. 129-60.

Freud, S. All references are to the Standard Edition (SE), by volume and page number.

Hillman, J. (1975) Re-Visioning Psychology, New York: Harper & Row.

Hillman, J. (1977) “An Inquiry into Image,” Spring: An Annual of Archetypal Psychology and Jungian Thought, pp. 62-88.

Hillman, J. (1979) The Dream and the Underworld, New York: Harper & Row.

Hillman, J., with Pozzo, L. (1983) Inter Views: Conversations with Laura Pozzo on Psychotherapy, Biography, Love, Soul, Dreams, Work, Imagination, and the State of the Culture, New York: Harper & Row.

Hillman, J. (1991) “The Great Mother, Her Son, Her Hero, and the Puer,” in P. Berry (ed.), Fathers and Mothers, Dallas, TX: Spring Publications, pp. 166-209.

Hillman, J. (2004) Archetypal Psychology, Uniform Edition of the Writings of James Hillman, vol. 1, Putnam, CT: Spring Publications.

Jung, C.G. Except as below, all references are to the Collected Works (CW) by volume, page number, and paragraph.

Jung, C.G. (1988) Nietzsche’s Zarathustra: Notes of the Seminar Given in 1934-1939, ed. J.L. Jarrett, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2 vols.

Kristof, N.D. (October 10, 2006) “Talking with the Monsters,” New York Times: A25

Marlan, J. (2006) “Jan Marlan Interviews James Hillman,” IAAP Newsletter,26:191-5

Paris, G. (2007) Wisdom of the Psyche” Depth Psychology After Neuroscience, London and New York: Routledge.

Perls, F. (1969) Gestalt Therapy Verbatim, ed. J.O. Stevens, Lafayette, CA: Real People Press.

Rove, K. (August 19, 2007) “FOX News Sunday with Chris Wallace.”

Sagan, C. (1977) The Dragons of Eden: Speculations on the Evolution of Human Intelligence, New York: Random House.

Simpson, J. (1980) British Dragons, London: B.T. Batsford.

Stevens, A. (1995) Private Myths: Dreams and Dreaming, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Thompson, S. (1955) Motif-Index of Folk Literature, Bloomington, IN, and London: Indiana University Press, 6 vols.

Vandam, J. (February 11, 2007) “Hard Times Fall on an Ill-Loved Hero,” MNew York Times, City Section: 8.

Watkins, M. (1984) Waking Dreams, Dallas, TX: Spring Publications.

Whitehead, A.N. (1967) Science and the Modern World, New York: Free Press.

Whitmont, E.C., and Perera, S.B. (1989) Dreams, A Portal to the Source, London and New York: Routledge.

Williams, D. (1996) Deformed Discourse: The Function of the Monster in Mediaeval Thought and Literature, Montreal and Kingston, London, and Buffalo: McGill-Queen’s Press.