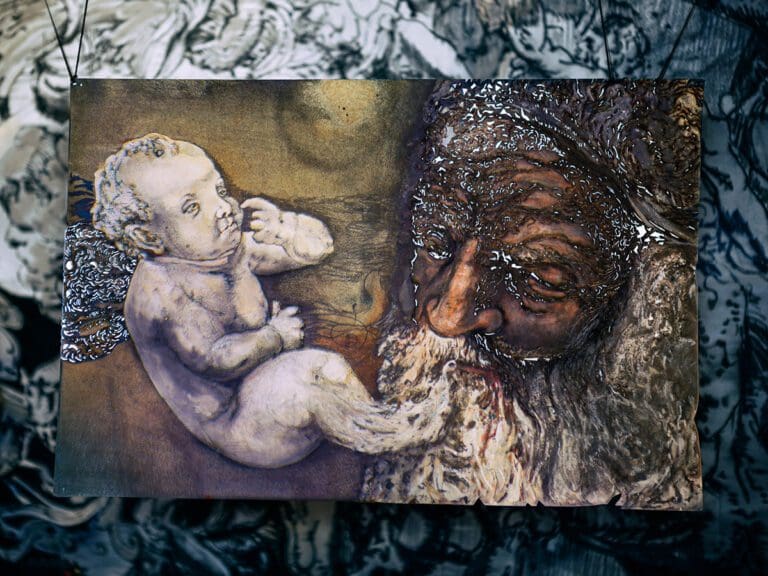

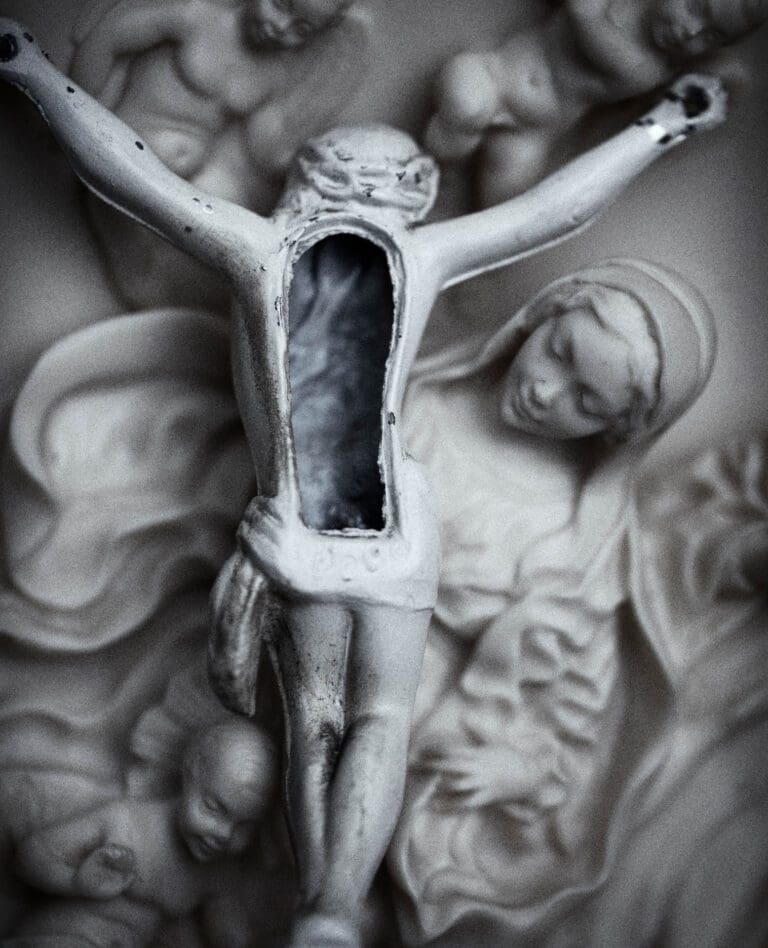

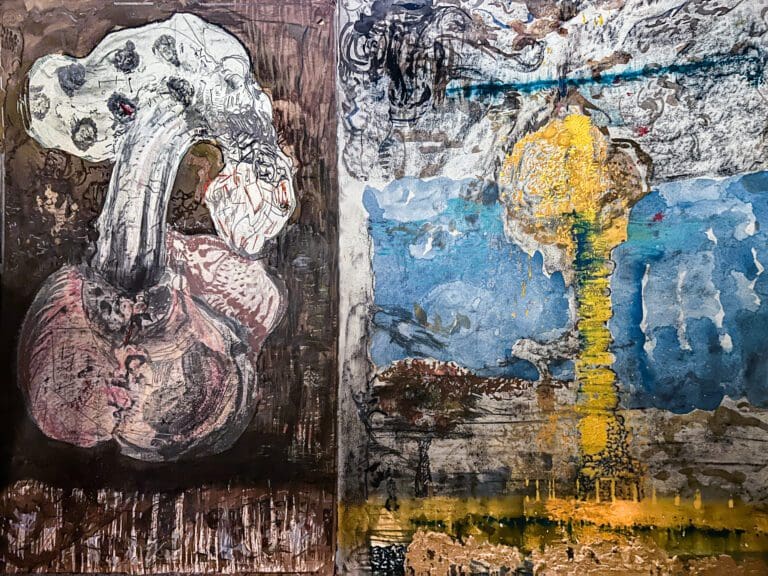

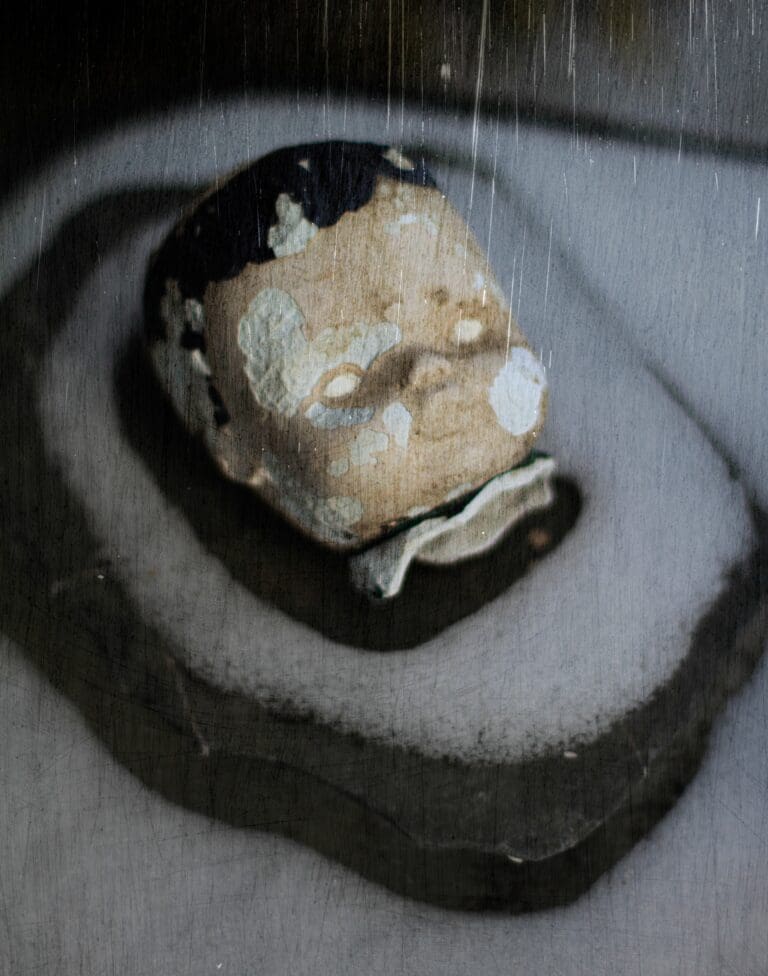

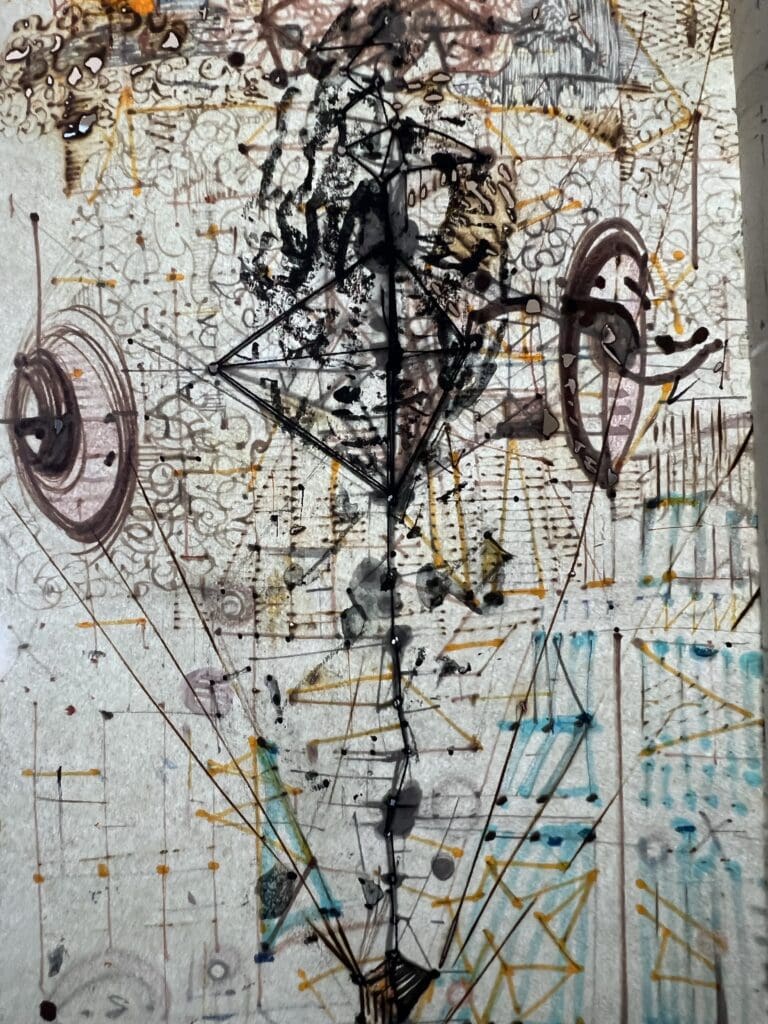

The process of a butterfly’s death and subsequent deterioration is a poignant testament to the ephemeral beauty of life, a study in the cyclical nature of existence. It is a procedure no less magnificent than their storied metamorphosis from caterpillar to winged wonder, showcasing the ephemeral yet meaningful existence of these creatures.

To begin, the process of dying in butterflies, like you and me, often involves visible slowing of movement and decreased responsiveness to external stimuli. If observed under a microscope, this lethargy is evidenced by diminished motor coordination, slowed wing beats, and lessened mandible movement.

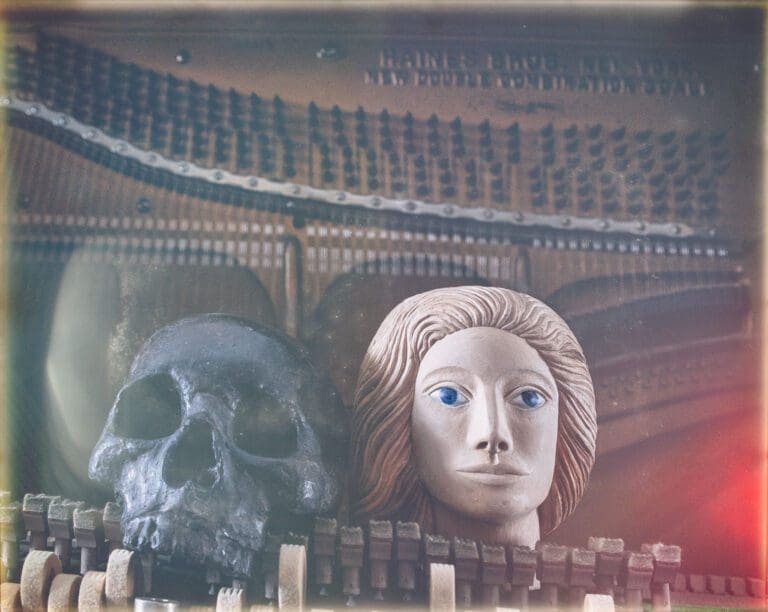

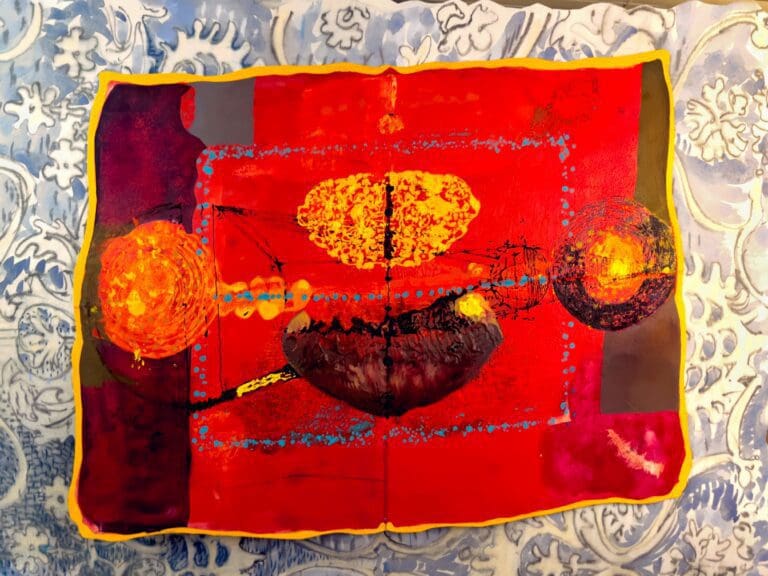

When a butterfly finally dies, its metabolic processes gradually cease. As the butterfly’s cells no longer produce energy, there’s a cessation of heartbeat and cessation of nerve function. Under the microscope, one might see the cells darkening, as their contents coagulate and lose structure. This is due to the cessation of homeostasis within the cells, which leads to autolysis or self-digestion.

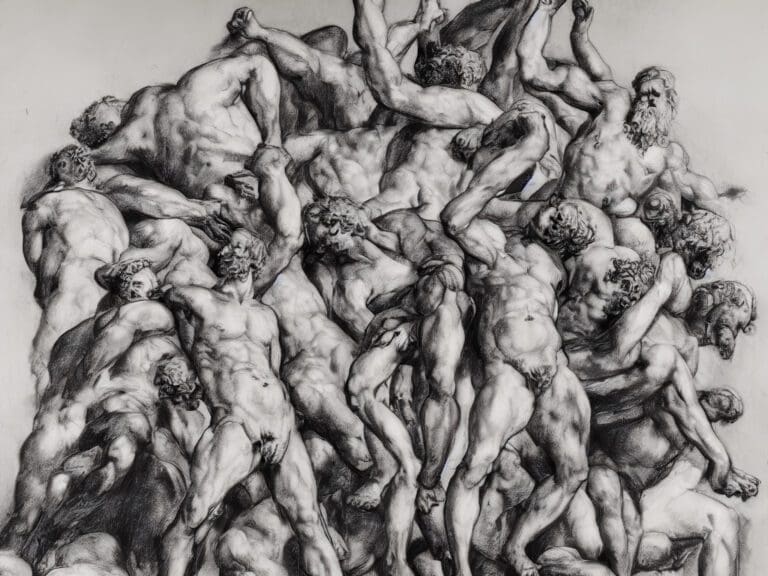

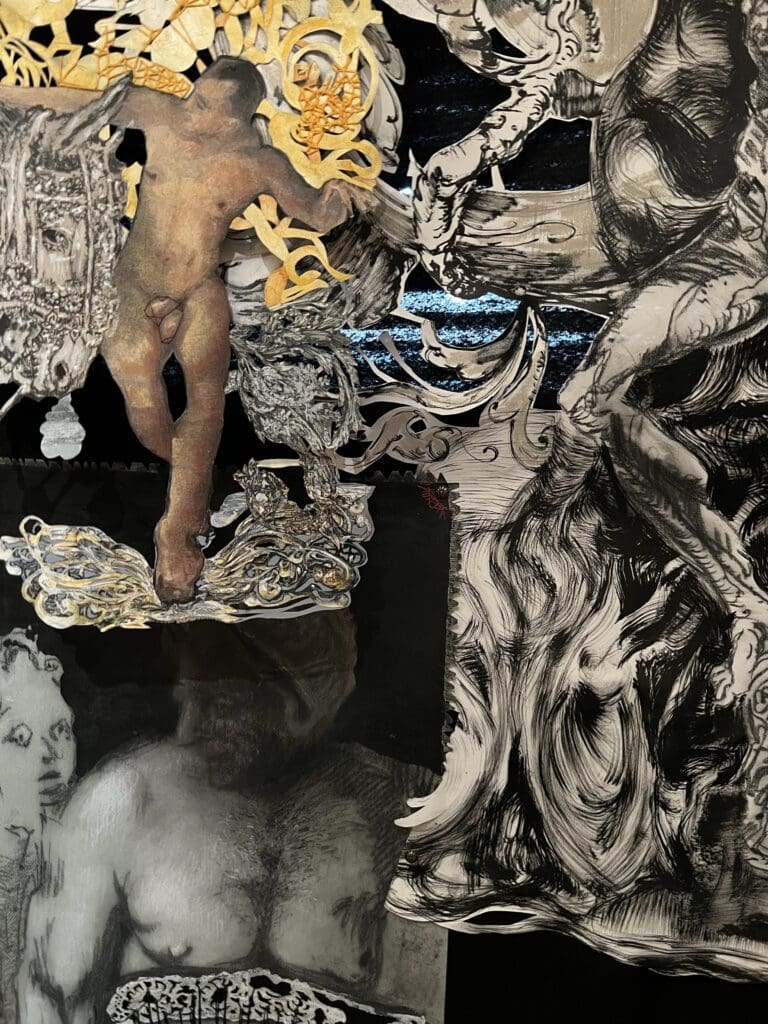

At a microscopic level, the deterioration process becomes markedly more fascinating and complex. Cell death begins as soon as the butterfly dies. Without the function of repair and upkeep from the now absent metabolic activity, the cells start to break down. Organelles within the cells, such as the mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum, start to degrade. This deterioration, under a microscope, might appear as a loss of distinct borders within cells and a general disorganization of internal structures.

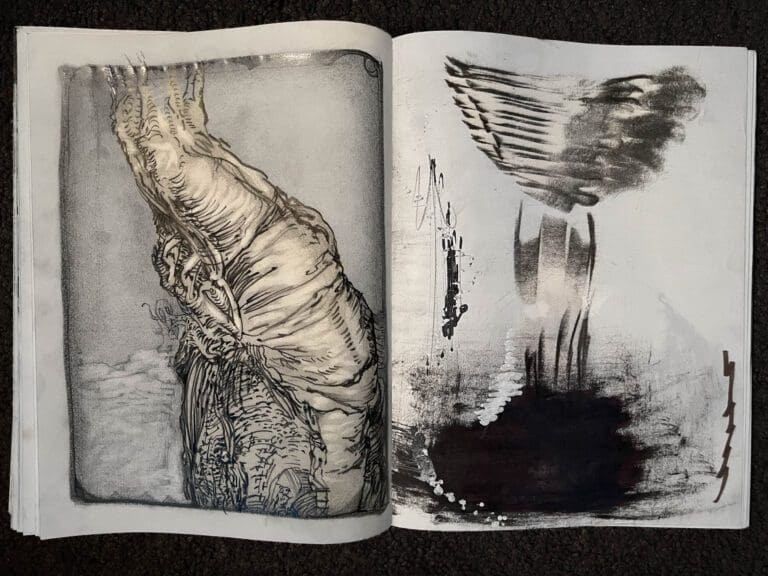

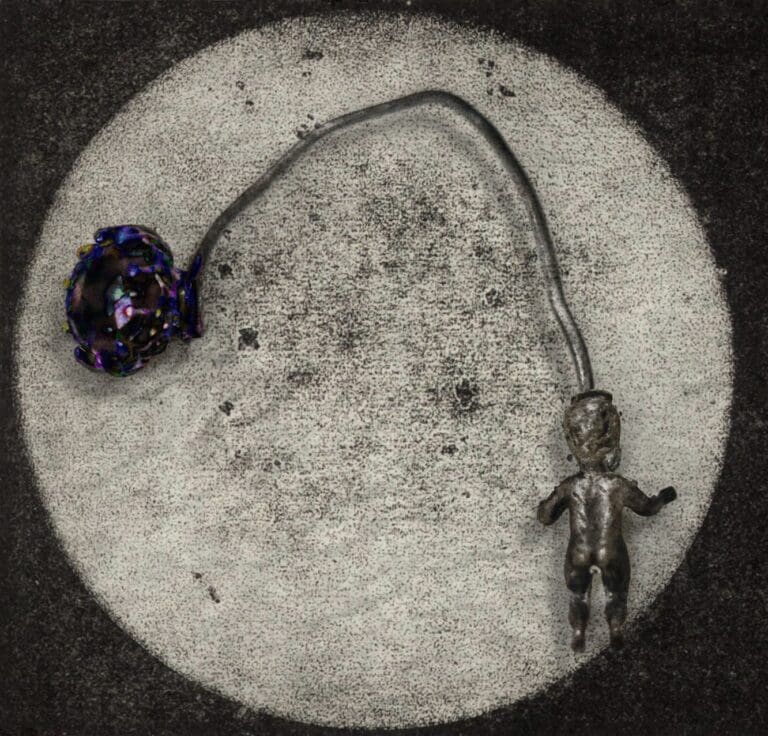

Meanwhile, bacteria present on the butterfly’s body and in its gut initiate their part of decomposition. In the earliest stages, these microscopic creatures proliferate rapidly, consuming the butterfly’s soft tissue. Under the microscope, you would see a burgeoning bacterial population, a burgeoning life within death itself. The bacteria would appear as rapidly moving and dividing entities, their mass and number gradually increasing.

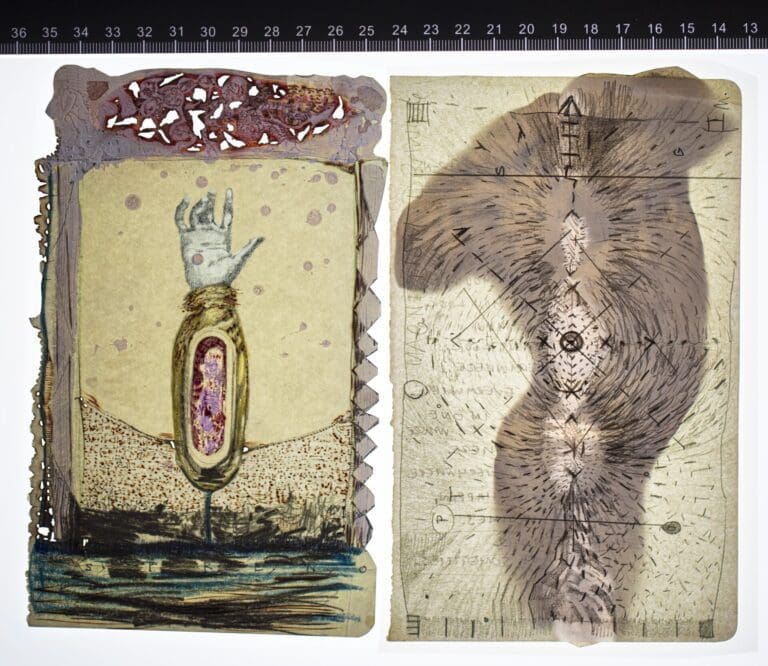

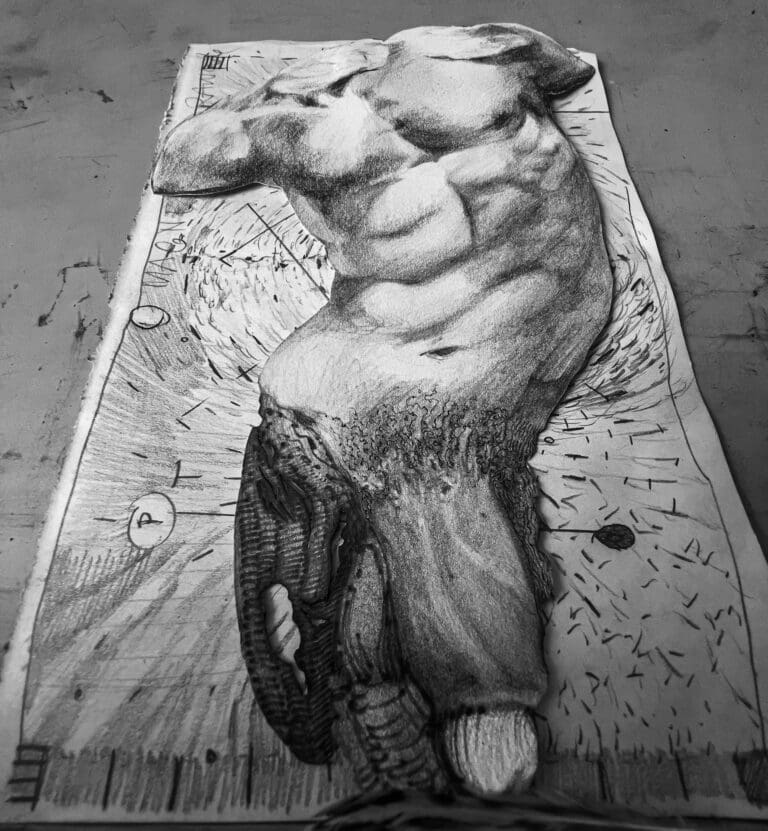

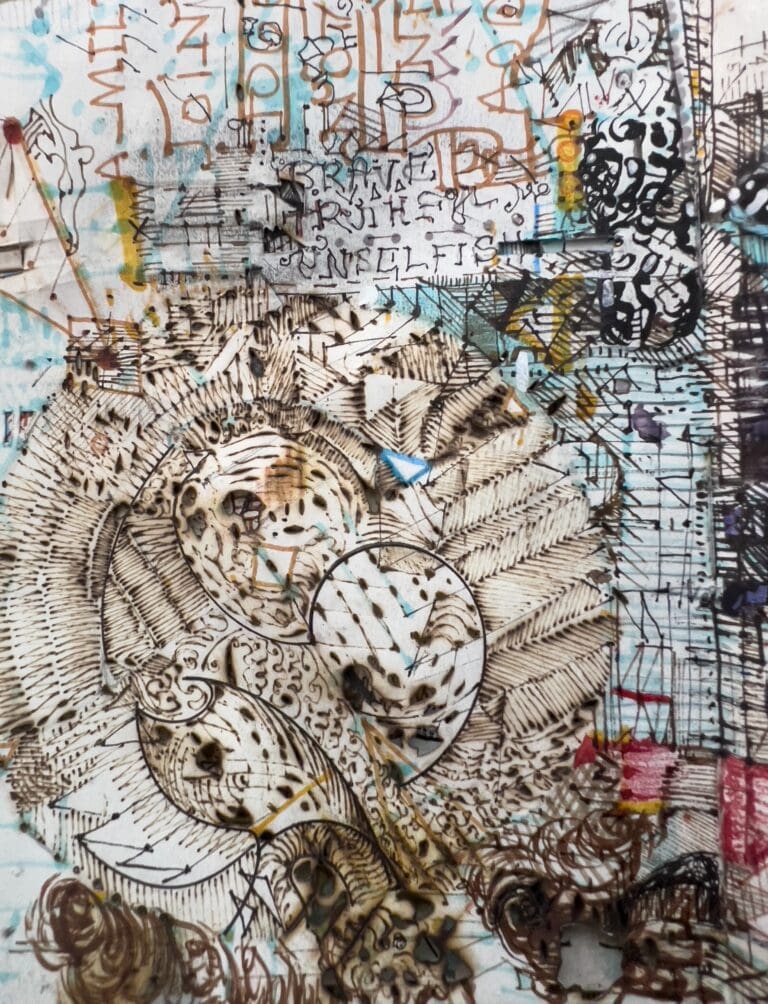

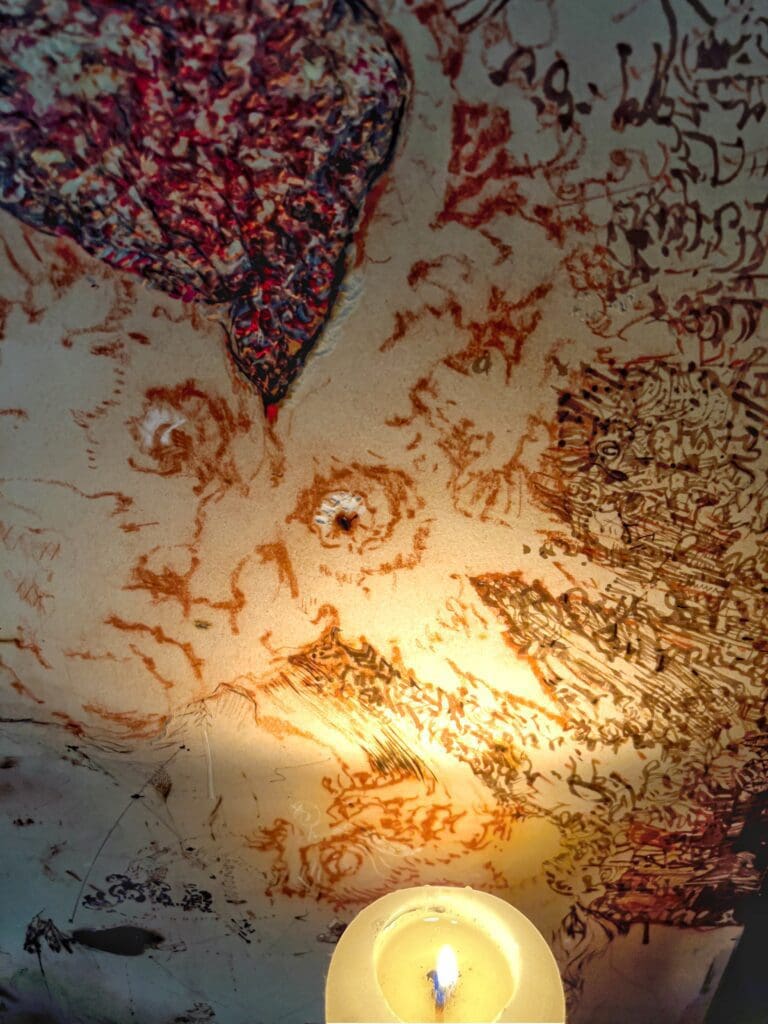

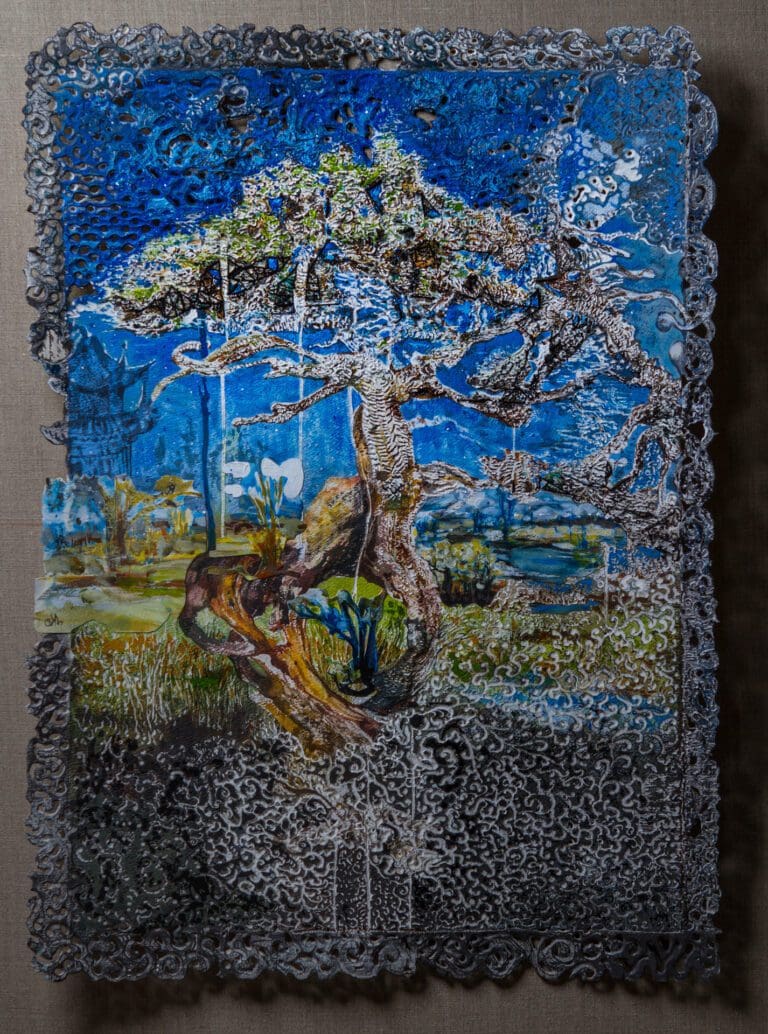

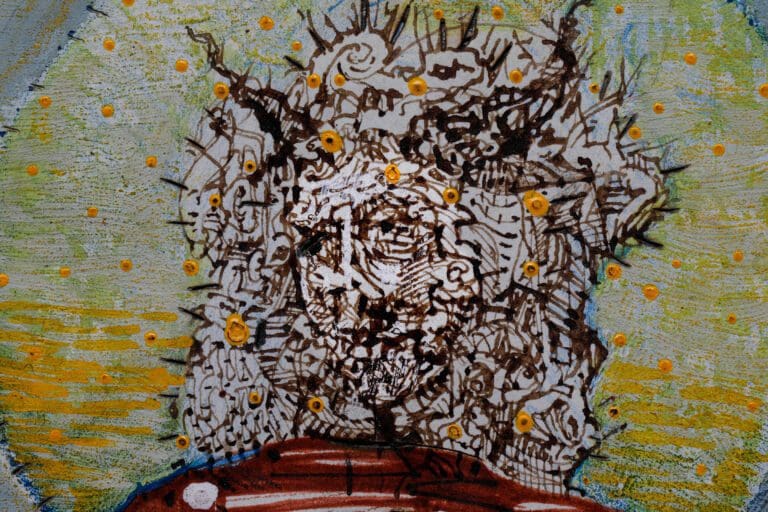

In time, the scales that cover the butterfly’s wings and give them their vibrant colors, begin to fall off. These scales are minuscule, overlapping like shingles on a roof, and under a microscope, they have a beautifully intricate structure, almost like a mosaic. As the butterfly decays, the adhesive that holds these scales loosens and the scales can easily be brushed off, leaving a powdery residue commonly referred to as ‘butterfly dust’.

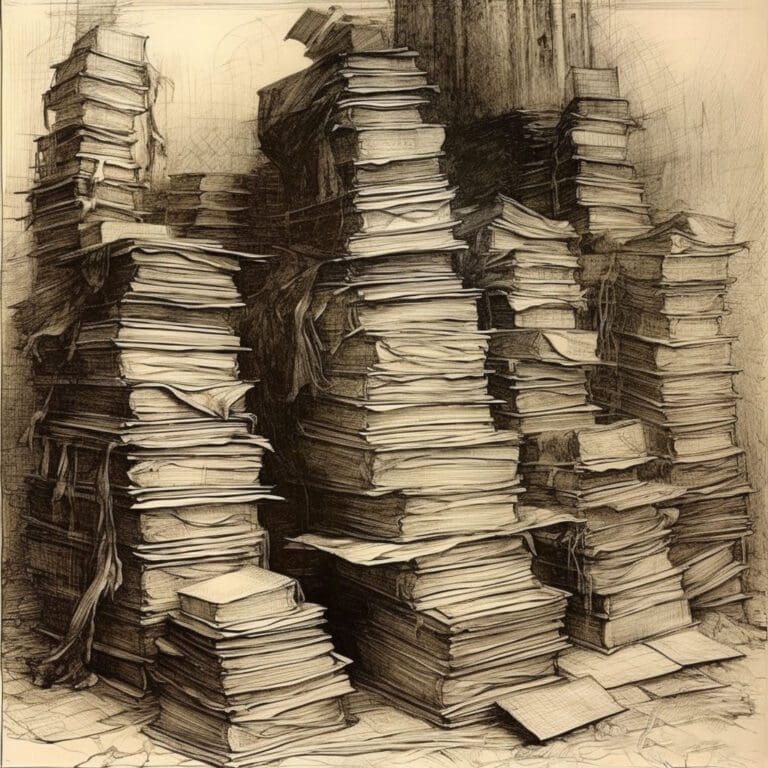

Over days and weeks, the butterfly’s physical form continues to break down under the relentless, yet necessary assault of decomposition. Fungi too, invisible to the naked eye, join the bacteria, contributing to the recycling of the butterfly back to the earth. Under a microscope, the sporulating hyphae of the fungi would look like delicate webs spreading over and within the butterfly’s body, further testament to the ceaseless cycles of nature.

While the death and deterioration of a butterfly may be viewed as a mournful event, it is a fundamental part of the circle of life. Without the ‘butterfly dust’ resulting from this intricate decomposition process, nutrients wouldn’t return to the soil to support the growth of the plants that future caterpillars (and eventually butterflies) will rely on. In this way, the beauty of the butterfly endures, long after the vibrant flashes of its wings have faded into the intricate dance of life and death.

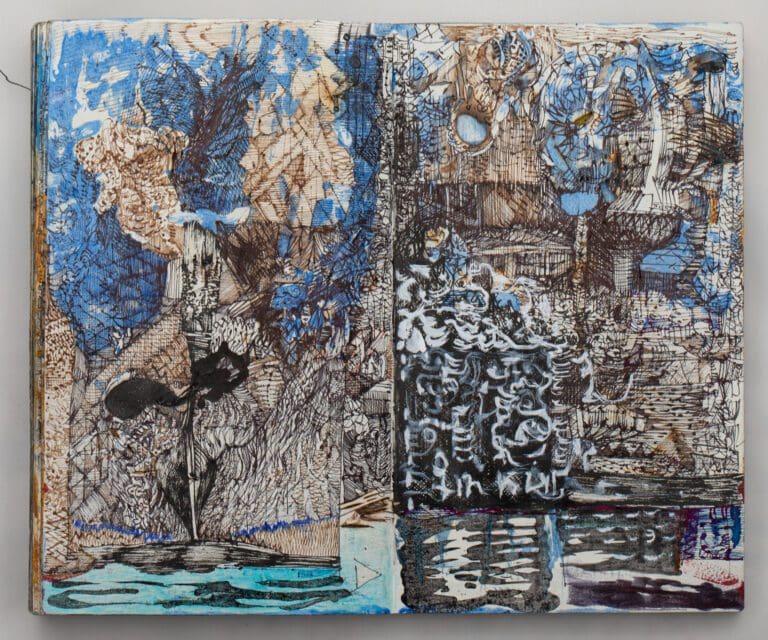

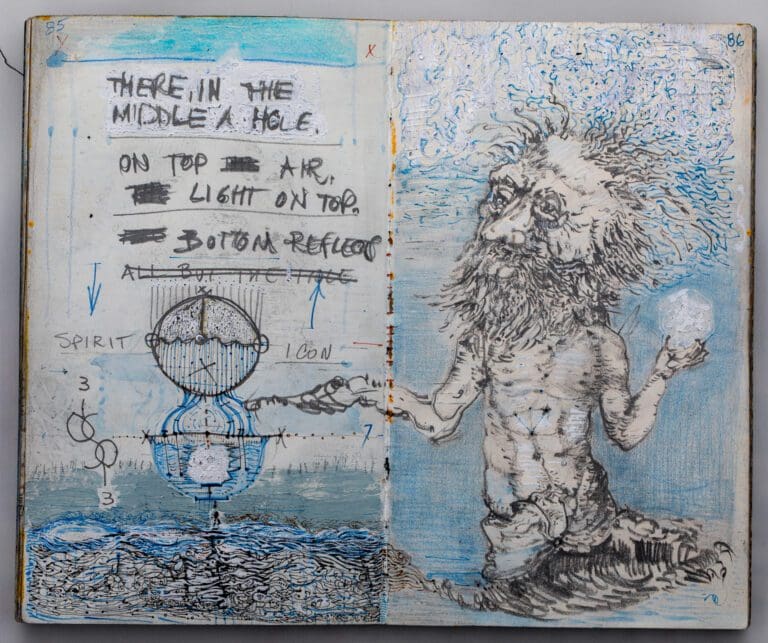

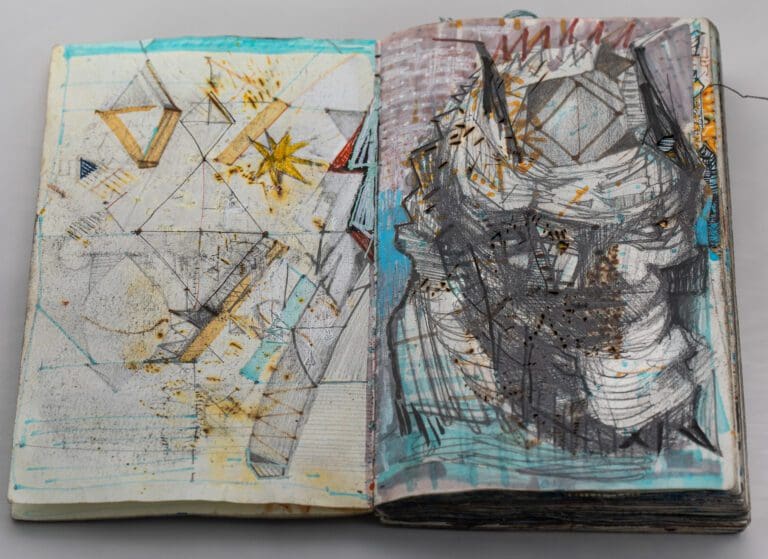

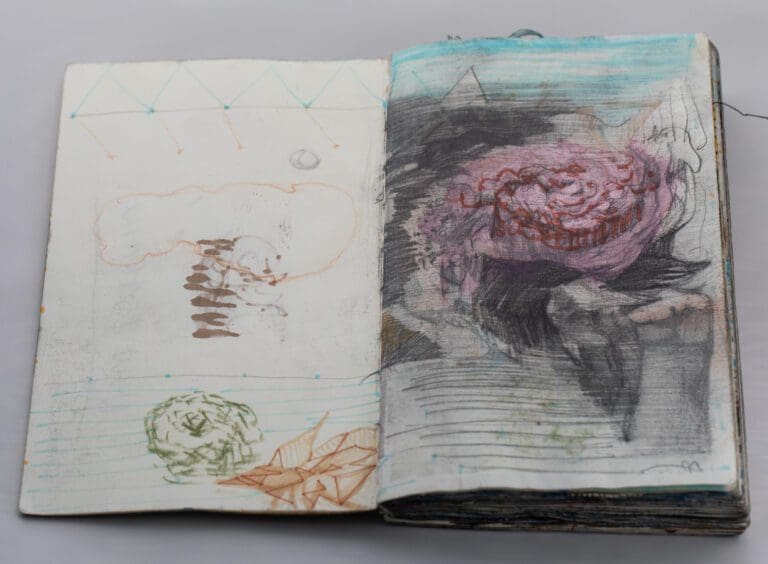

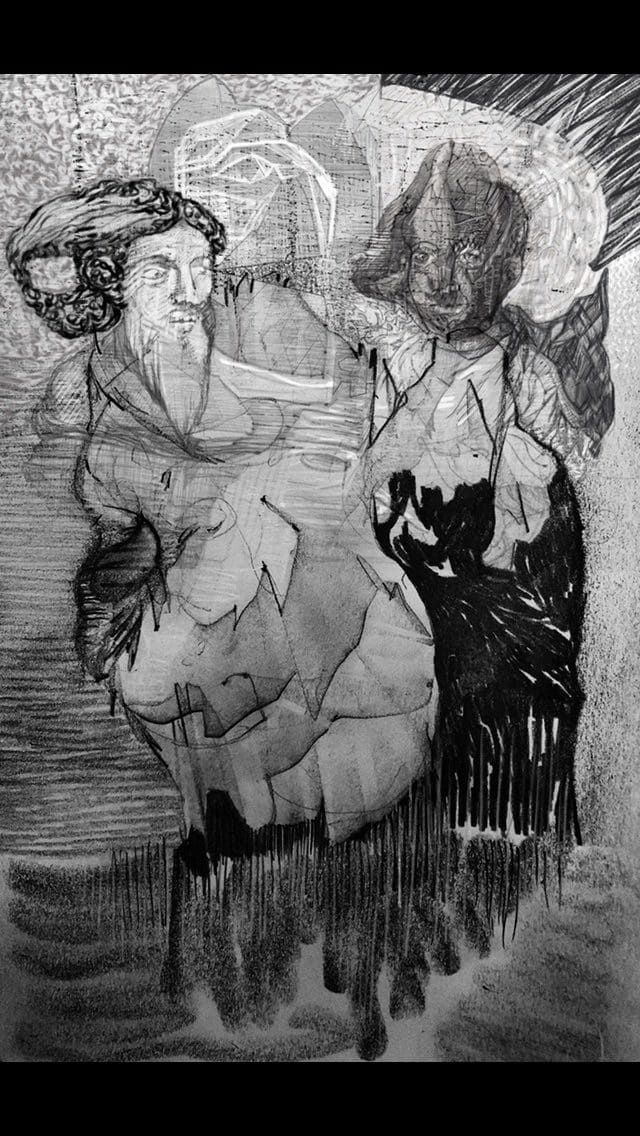

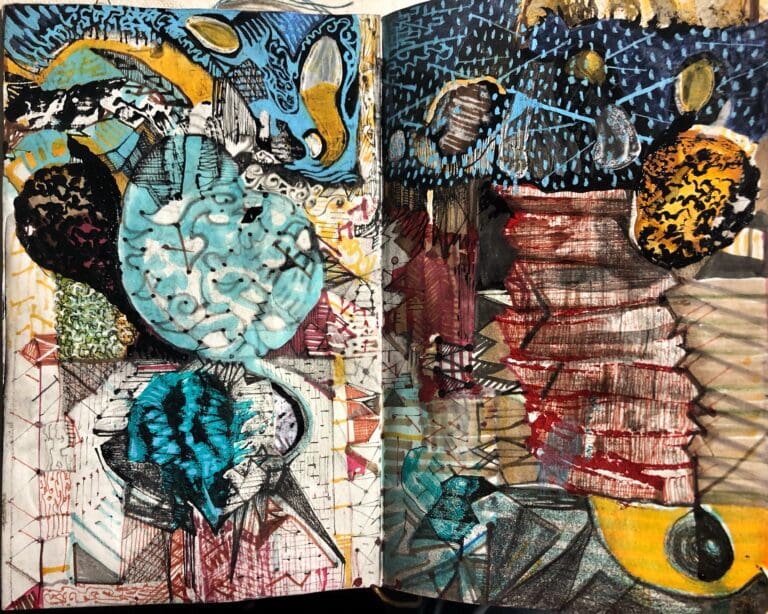

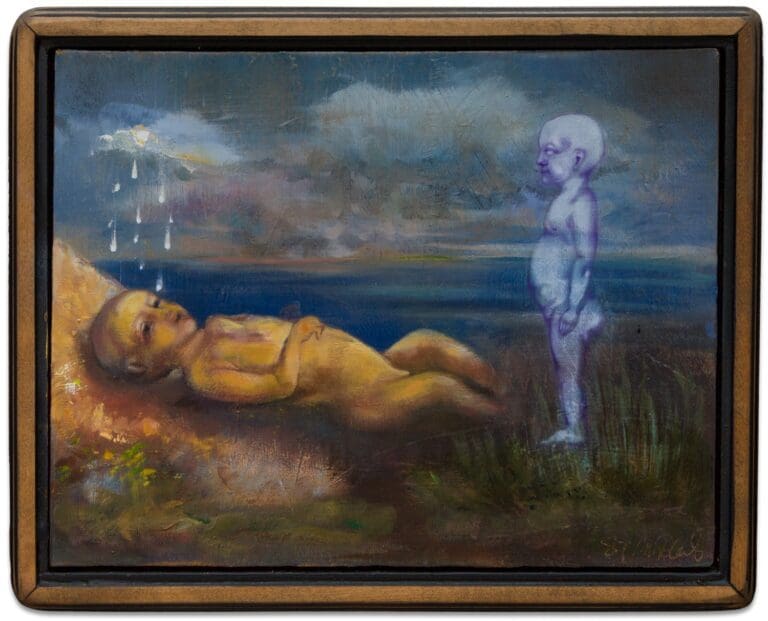

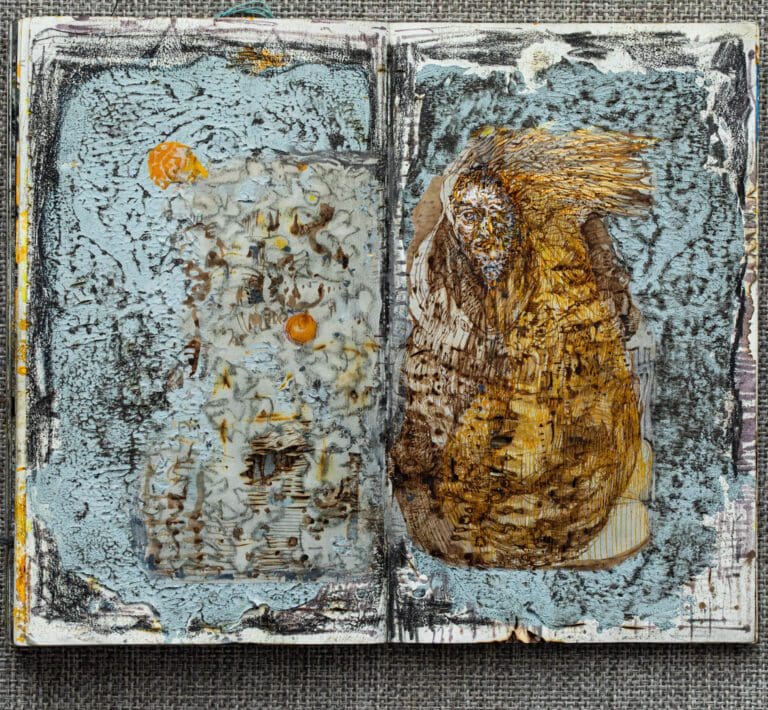

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”54″ sortorder=”608,611,610,614,613,612,609″ display=”pro_mosaic”]

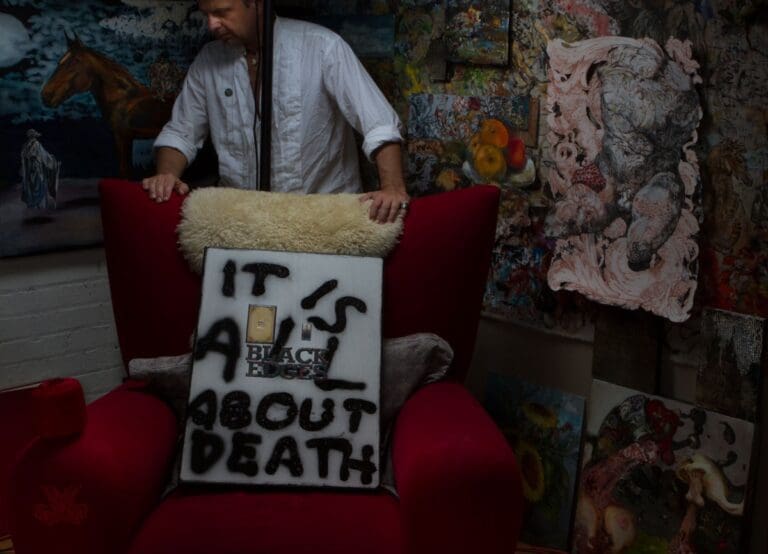

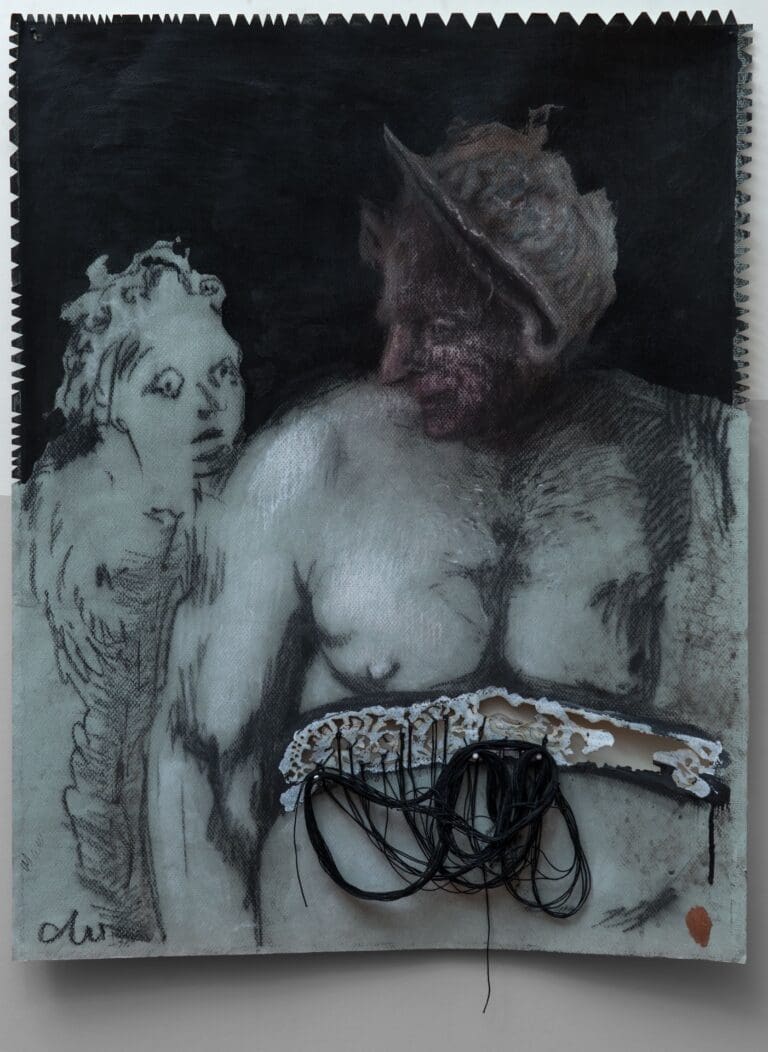

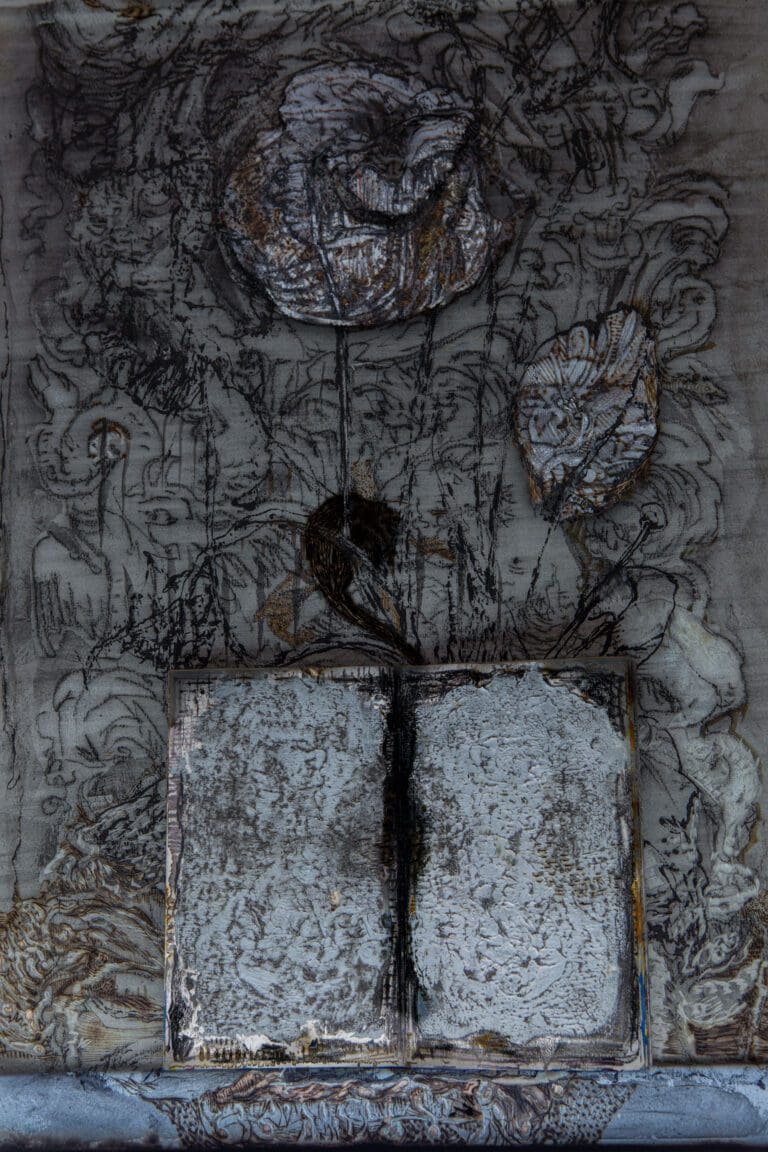

Folded in half,

Covered in dust,

If looks could kill,

Erect with lust.