The Torso, not the Head

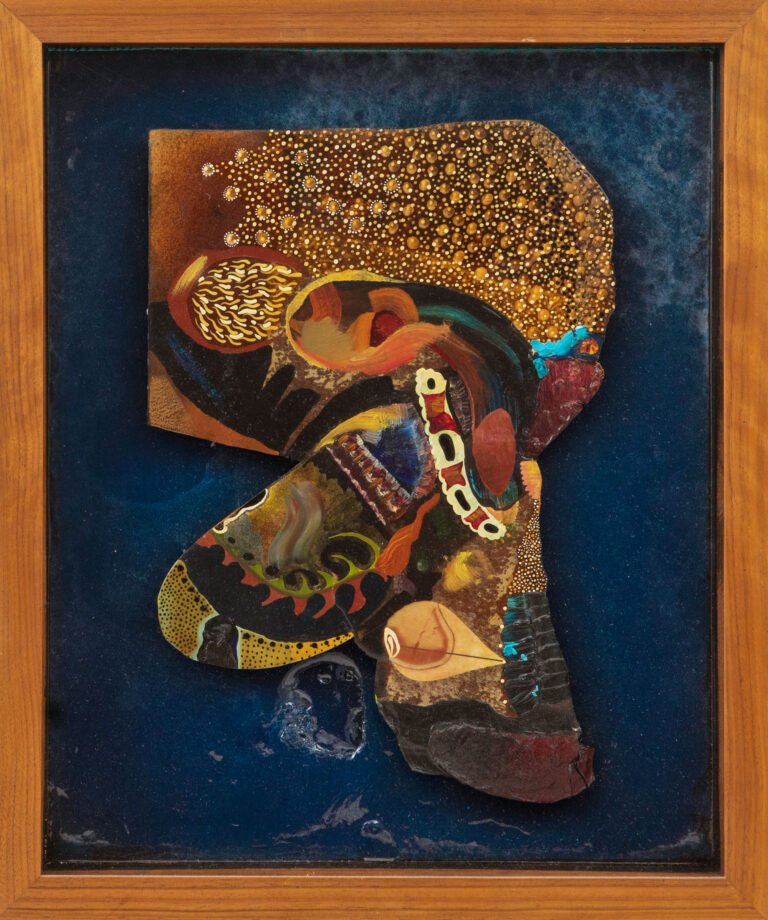

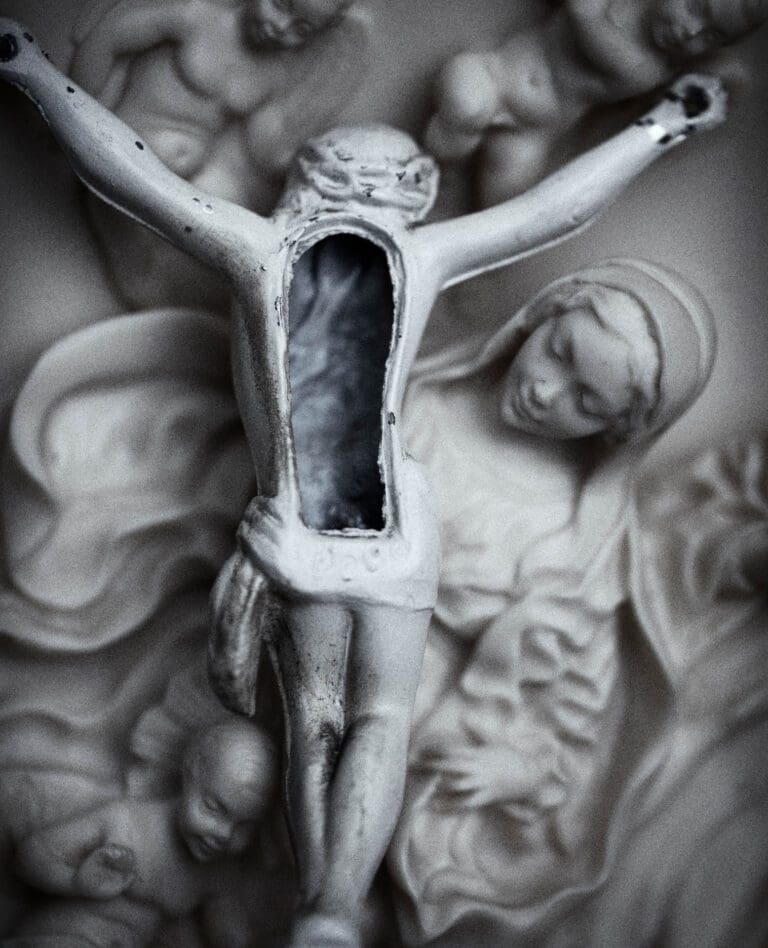

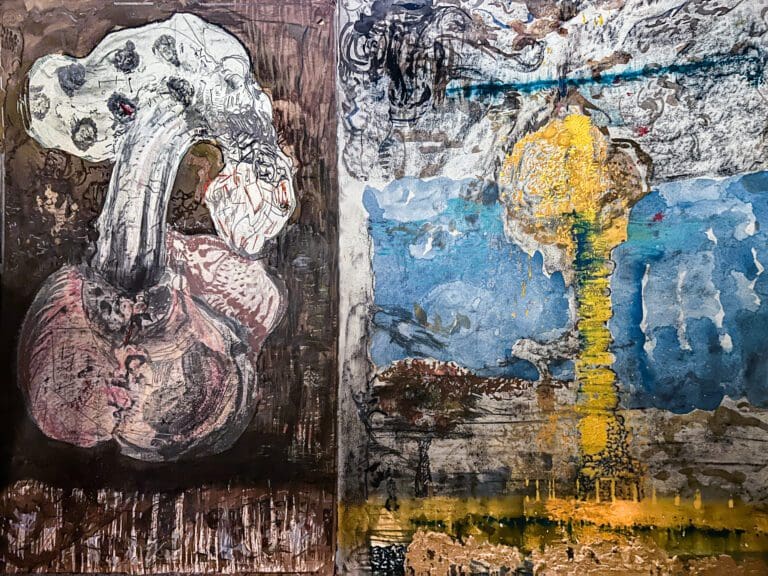

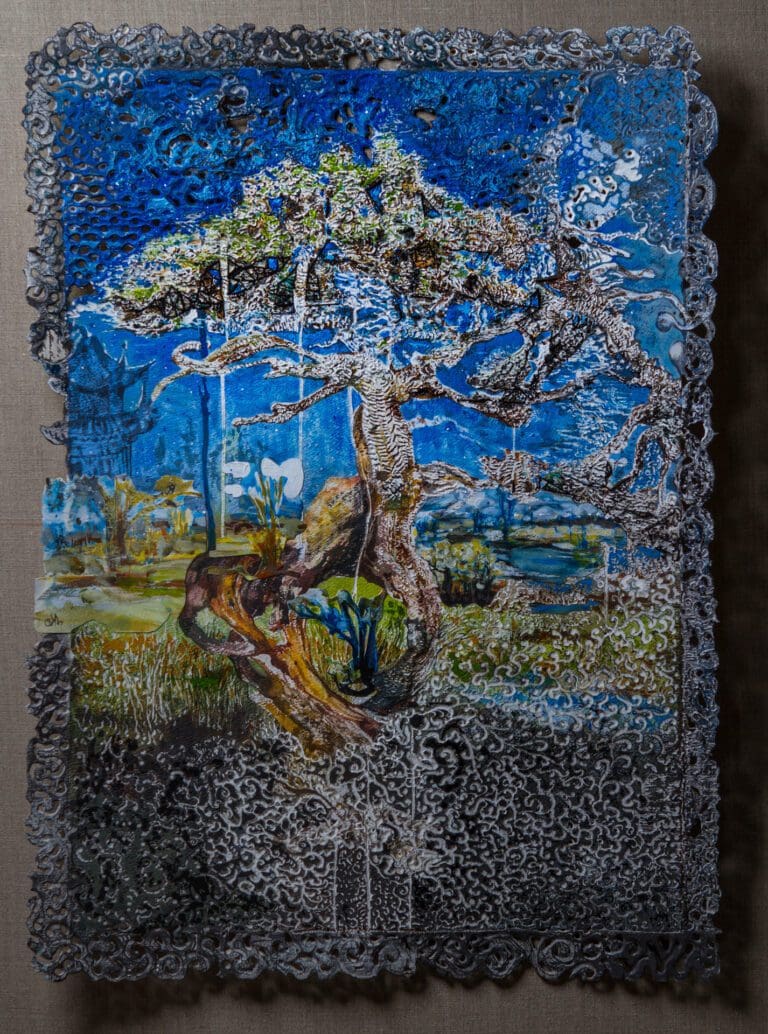

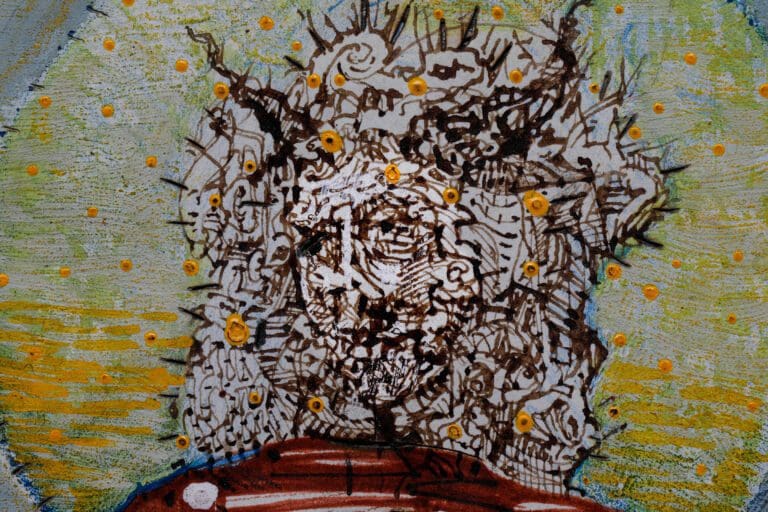

In the quiet corridors of history, strewn with broken marble, lies the evidence of humanity’s timeless quest for idealization. From the antiquities of Greece to the grandeur of the Renaissance, our tale unfolds, paradoxically, not in the complete figures of gods and heroes, but in the fragments left behind – the torso. The story of mankind, engraved in stone, often reduced to a core, a trunk of raw beauty.

In the quiet corridors of history, strewn with broken marble, lies the evidence of humanity’s timeless quest for idealization. From the antiquities of Greece to the grandeur of the Renaissance, our tale unfolds, paradoxically, not in the complete figures of gods and heroes, but in the fragments left behind – the torso. The story of mankind, engraved in stone, often reduced to a core, a trunk of raw beauty.

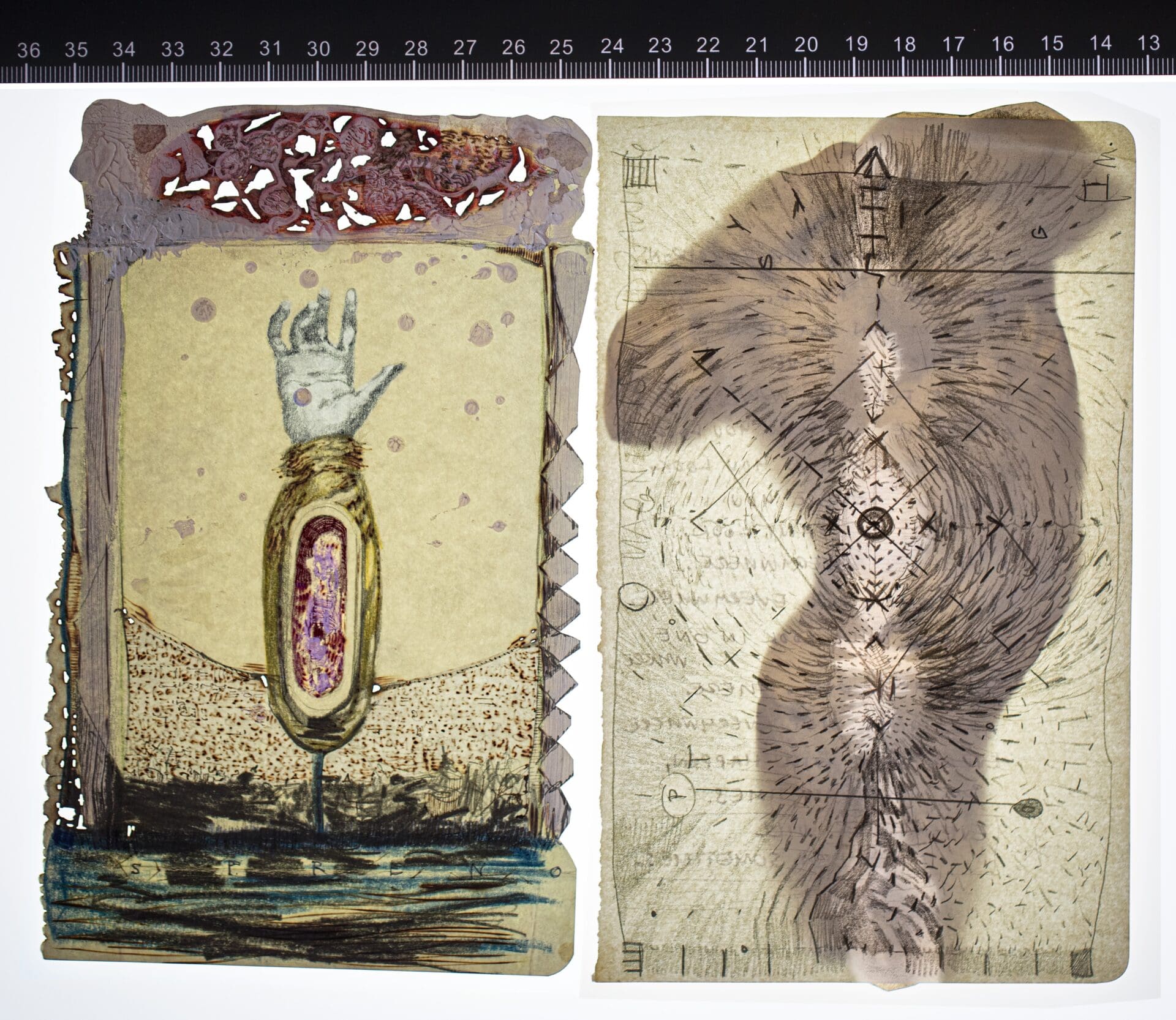

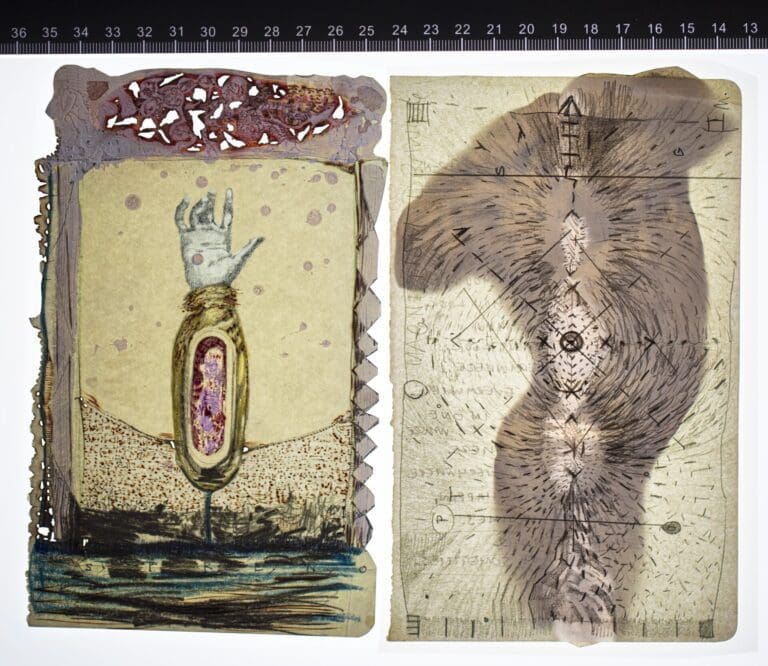

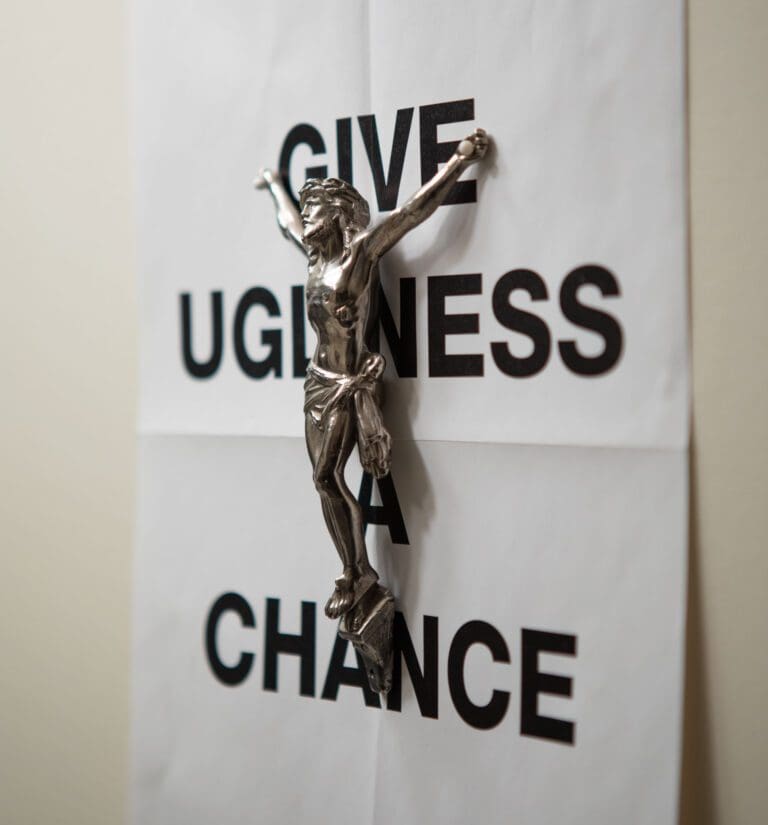

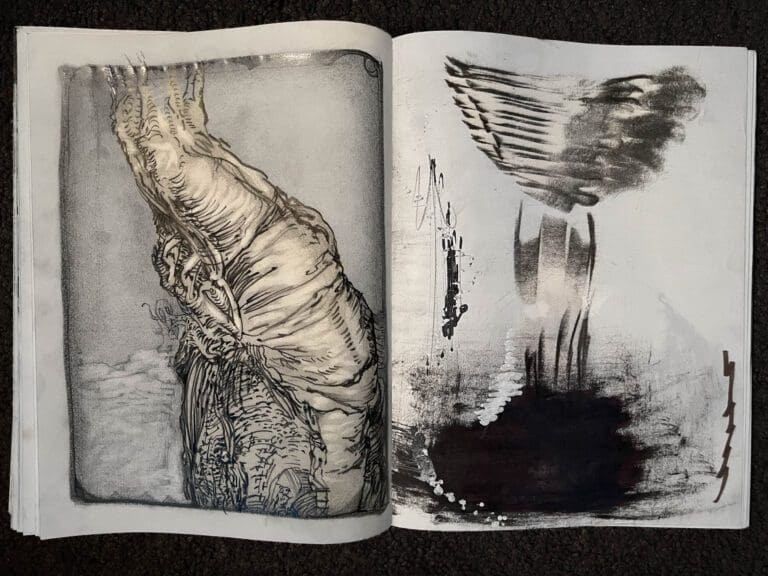

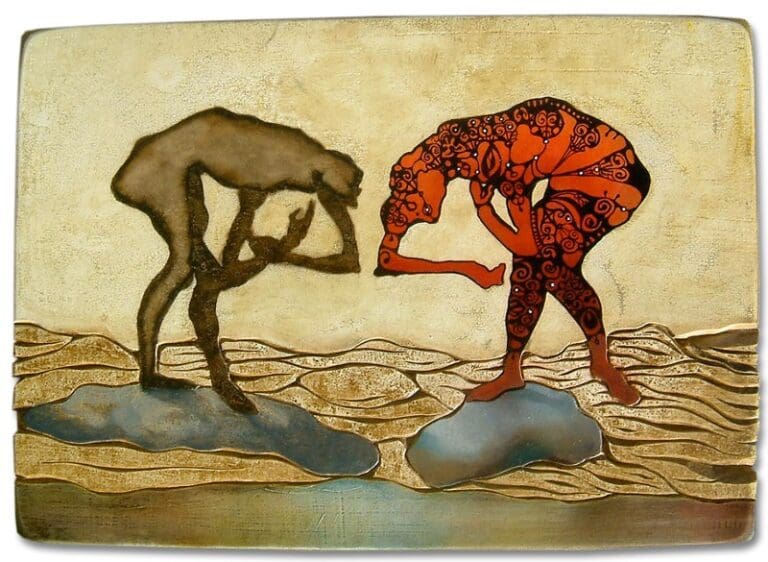

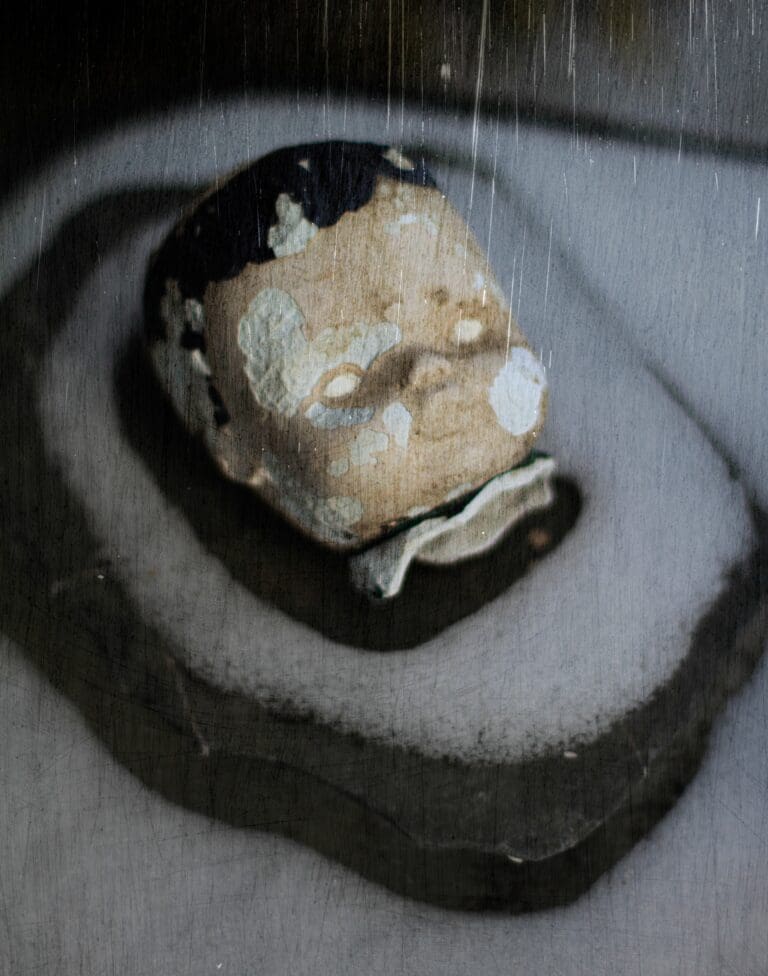

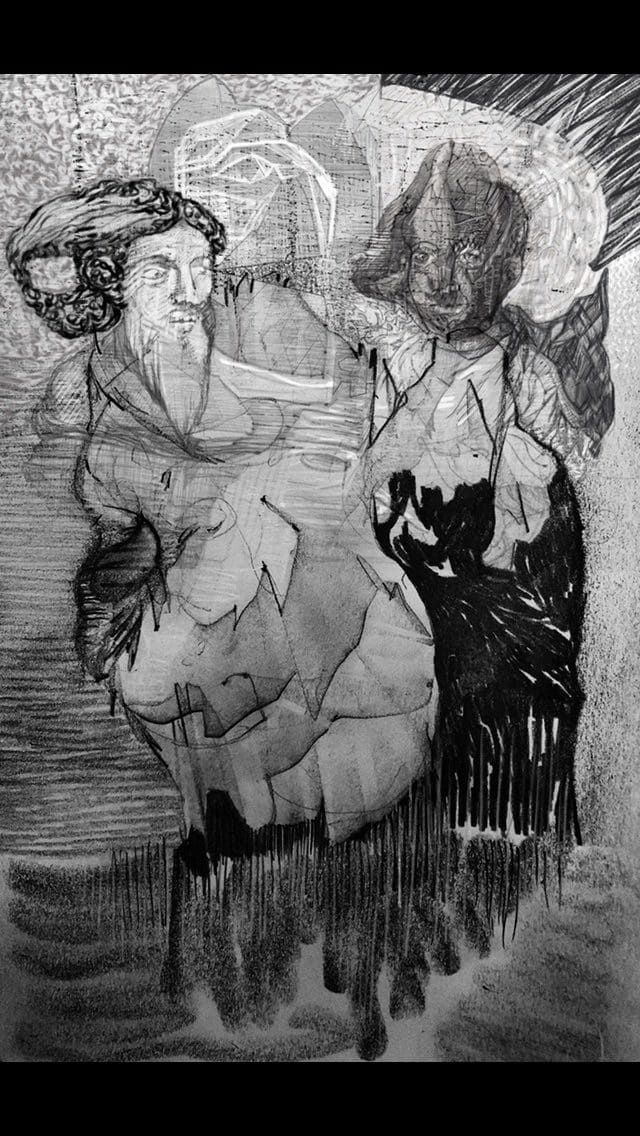

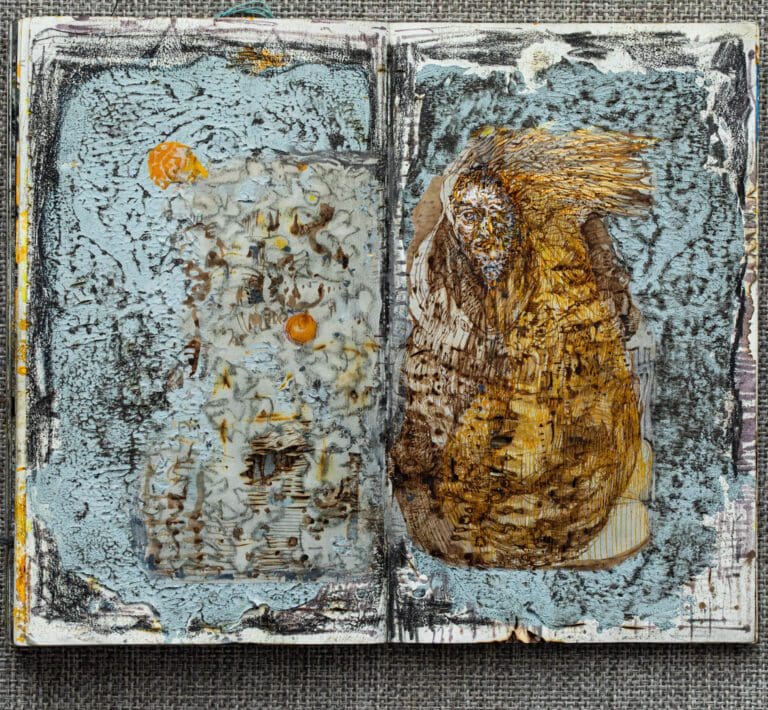

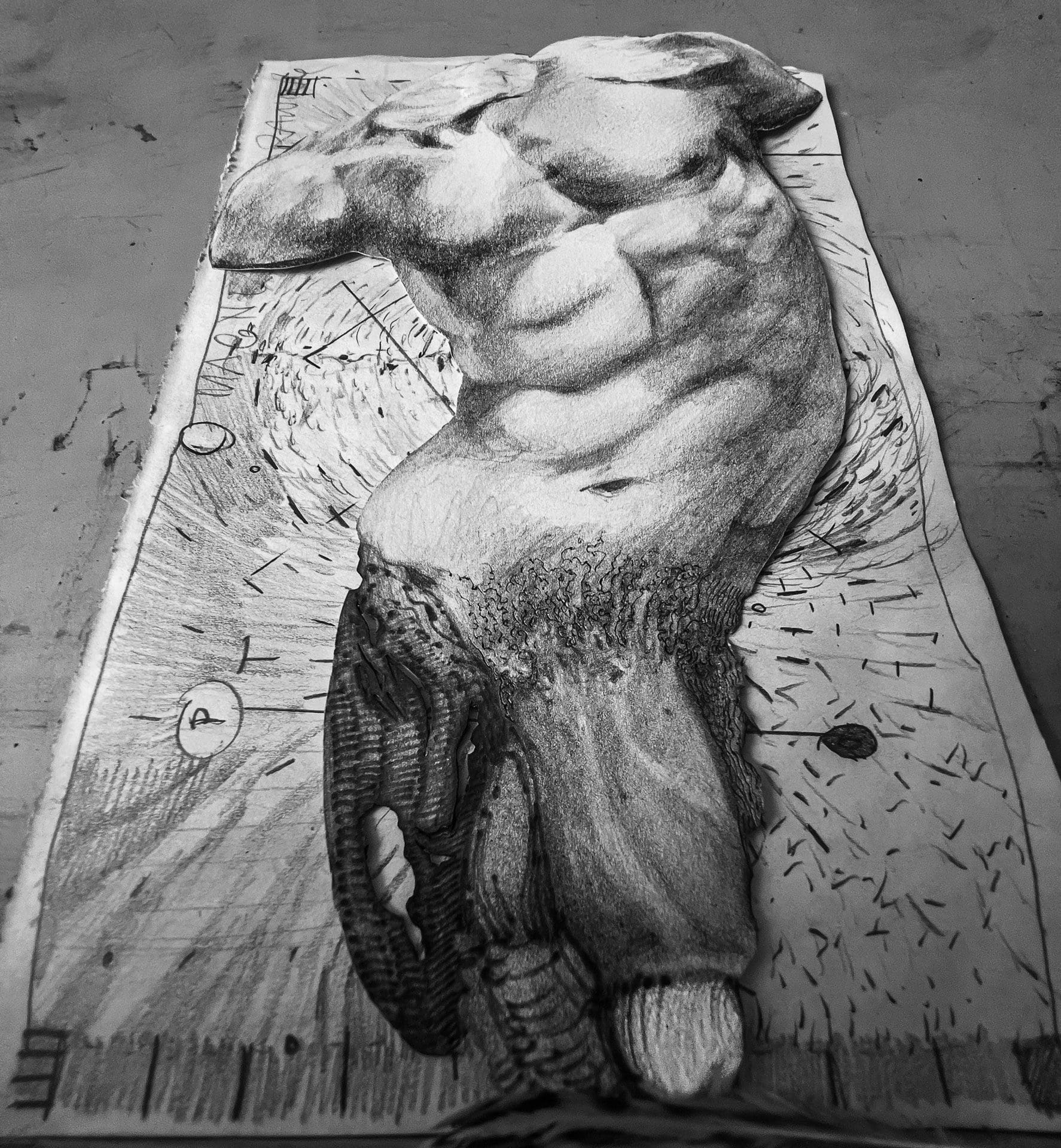

The torso, bereft of its extremities, head, and often its lower body, seems at first an incomplete narrative. Yet, therein lies its captivating allure. This paradox, the paradox of the incomplete embodying the ideal, thrums with a strange vitality that spans epochs, cultures, and civilizations.

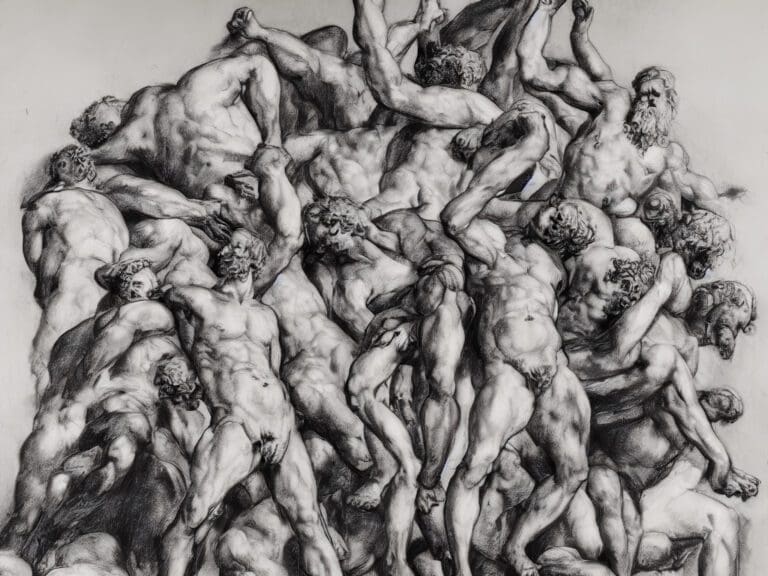

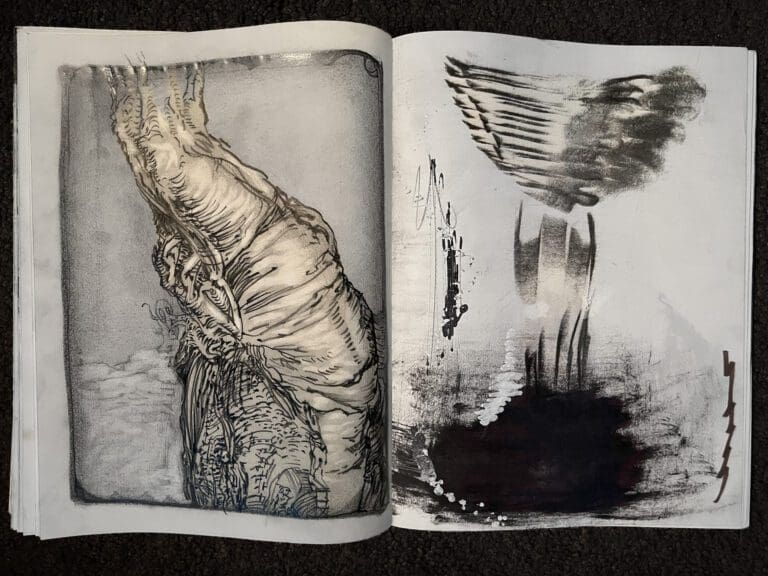

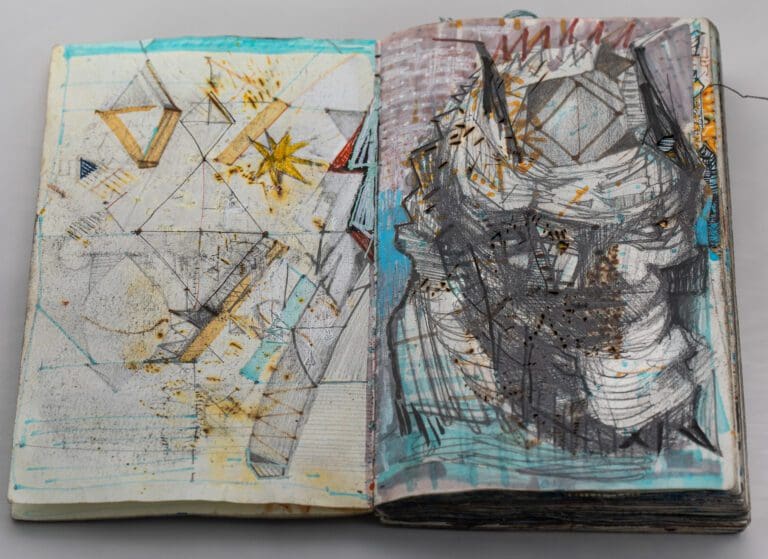

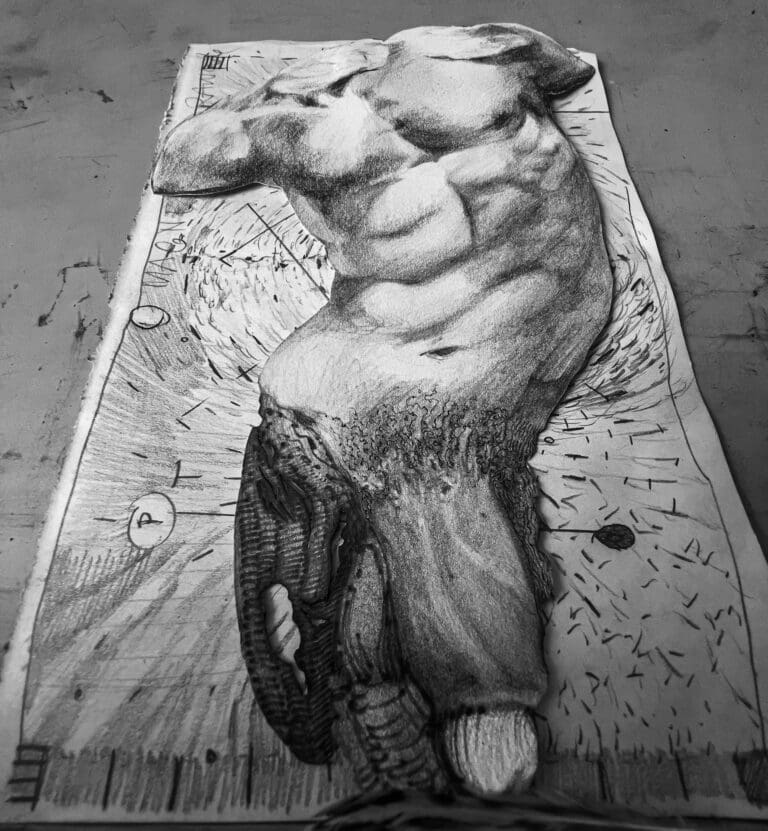

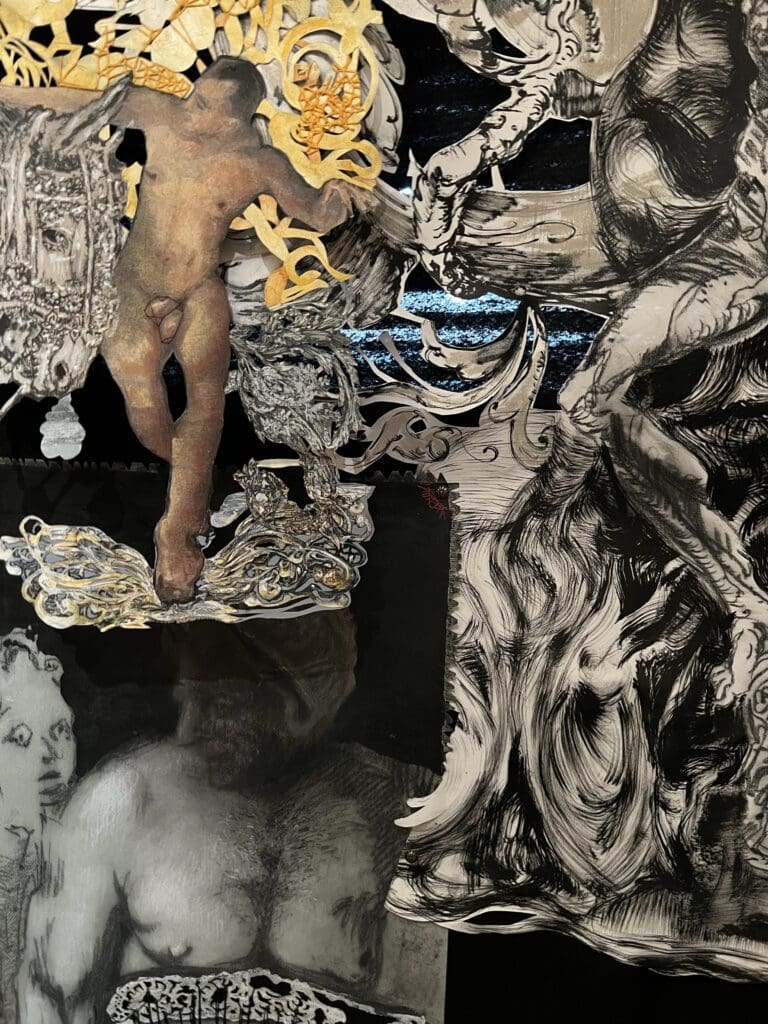

In the hallowed halls of the Renaissance, under the patient and diligent hands of sculptors like Michelangelo and Donatello, the human form was birthed anew. Yet, the ideal was not captured in the fluid lines of a complete statue, but in the intricate curve of a muscular chest, the gentle swell of a belly, the subtle lines that traced the spine. These craftsmen, maestros of marble, spoke to us not in complete stories, but in verses, in the tantalizing fragments of a torso.

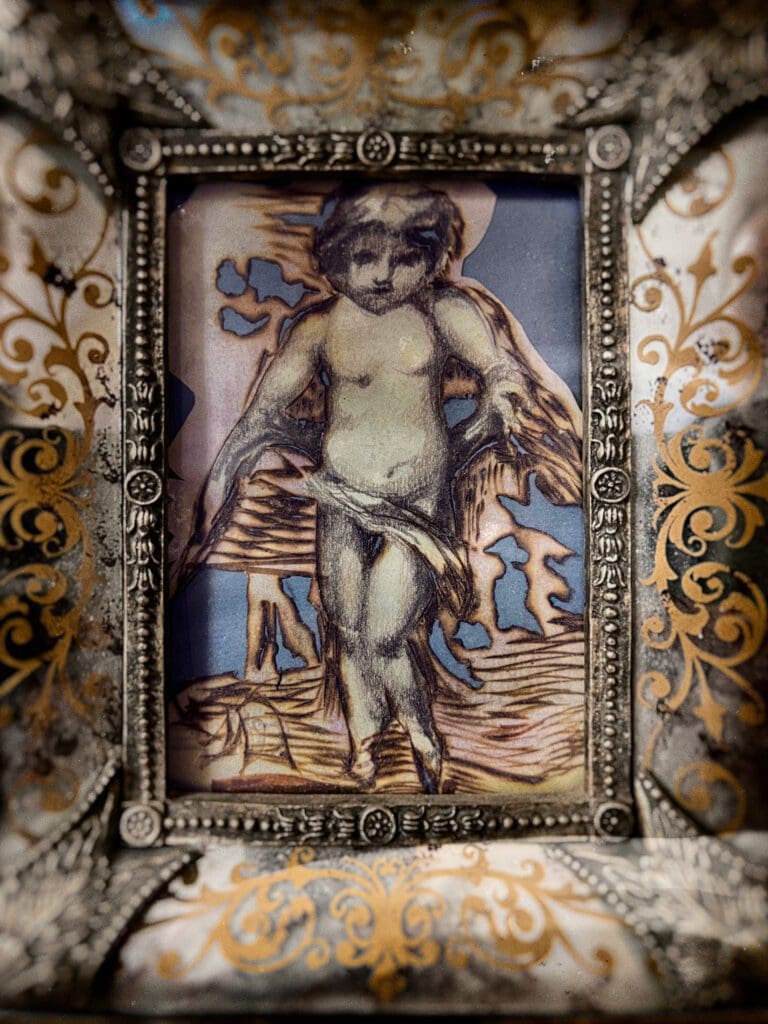

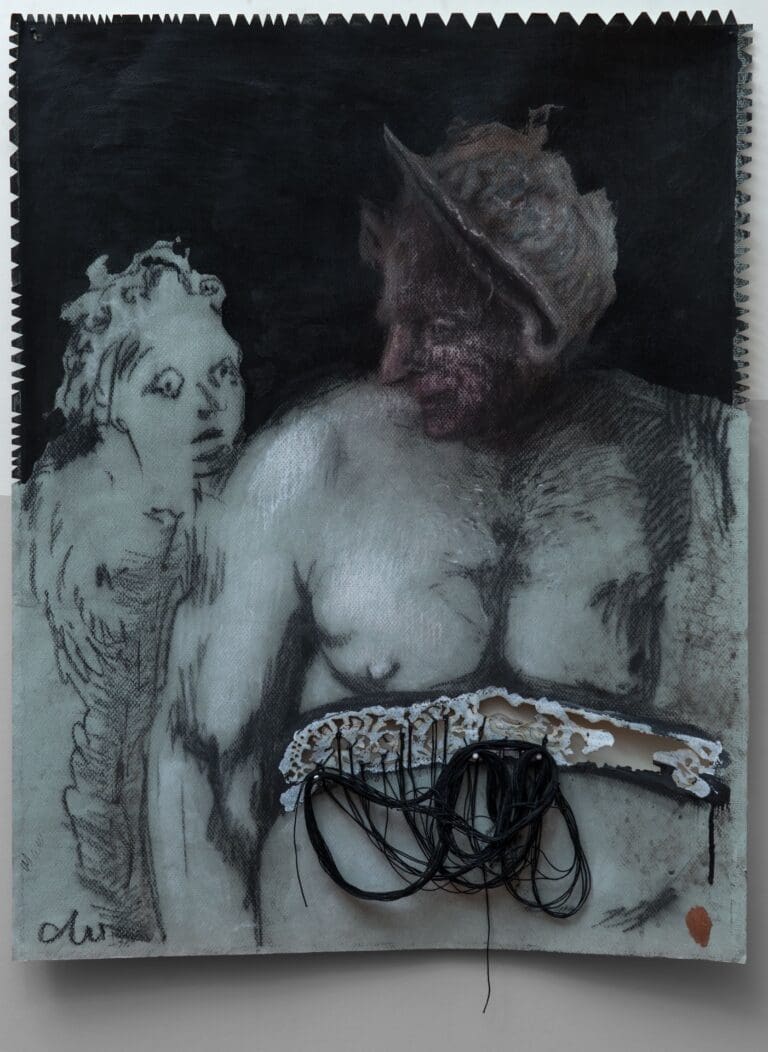

Strangely enough, while heads lost to time, limbs eroded by elements, the torso often survives, and so does the mystery of the genitals. It’s not so much about the carnal or the obscene, but rather the very essence of life, survival, and perpetuation of the species. In a way, these features serve as a symbol of enduring potency, a reminder of our human fragility and strength.

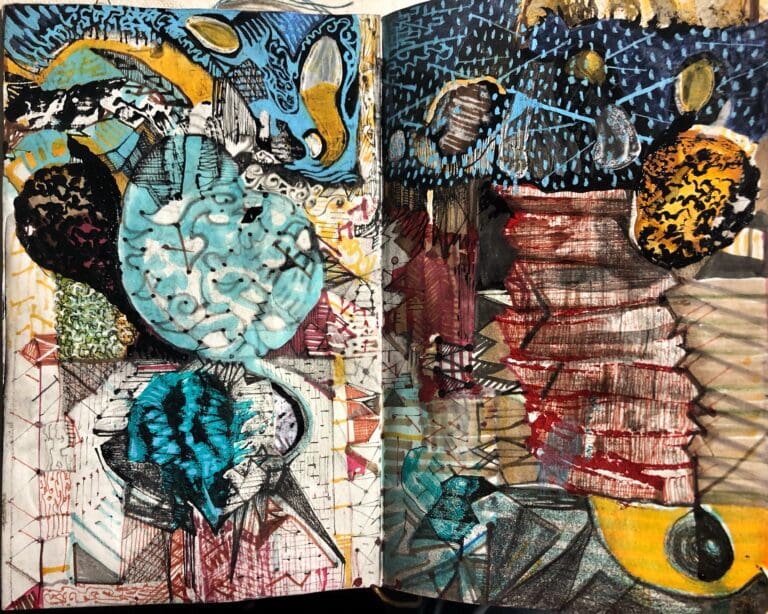

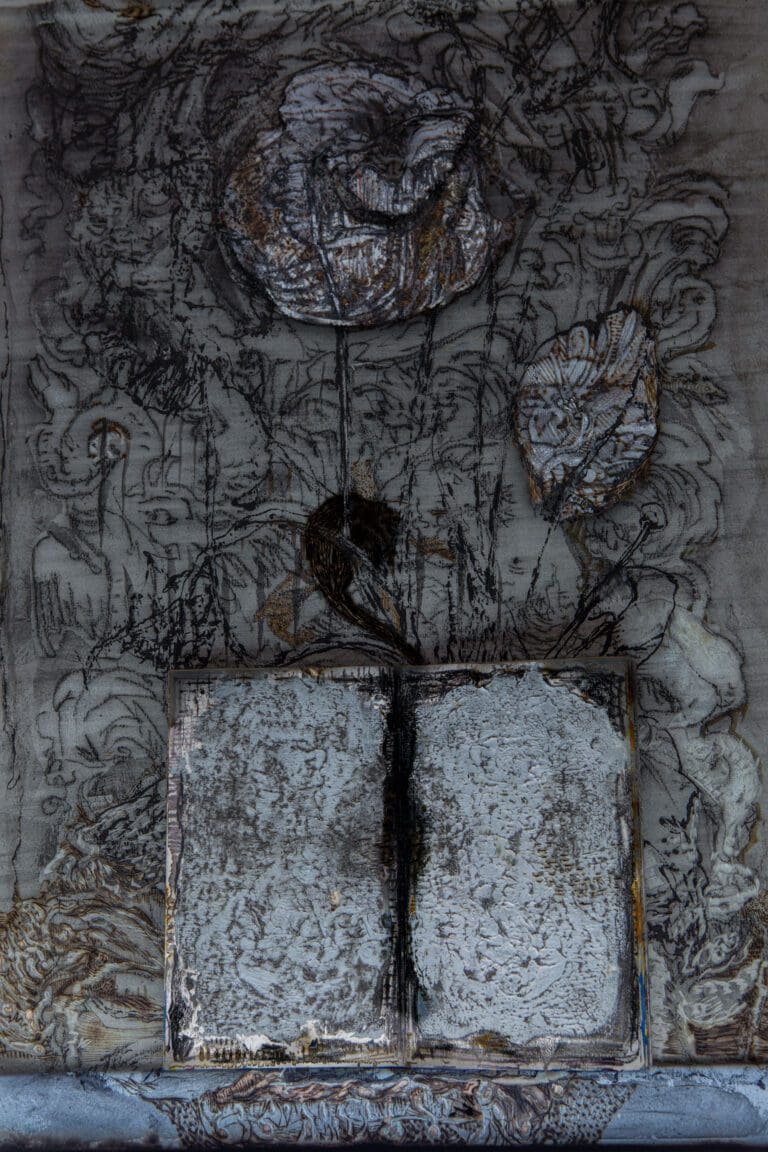

The power of the torso, the allure of the fragmented figure, lays in its invocation of imagination. Each fragment tells a story – one of heroism, divinity, ideal beauty, human frailty – yet the narrative remains open-ended. It invites the observer to ponder, to wonder, to reimagine what might have been. The missing parts are not defects but doors to an untold realm of stories and interpretations, making these shattered figures enigmatic and endlessly fascinating.

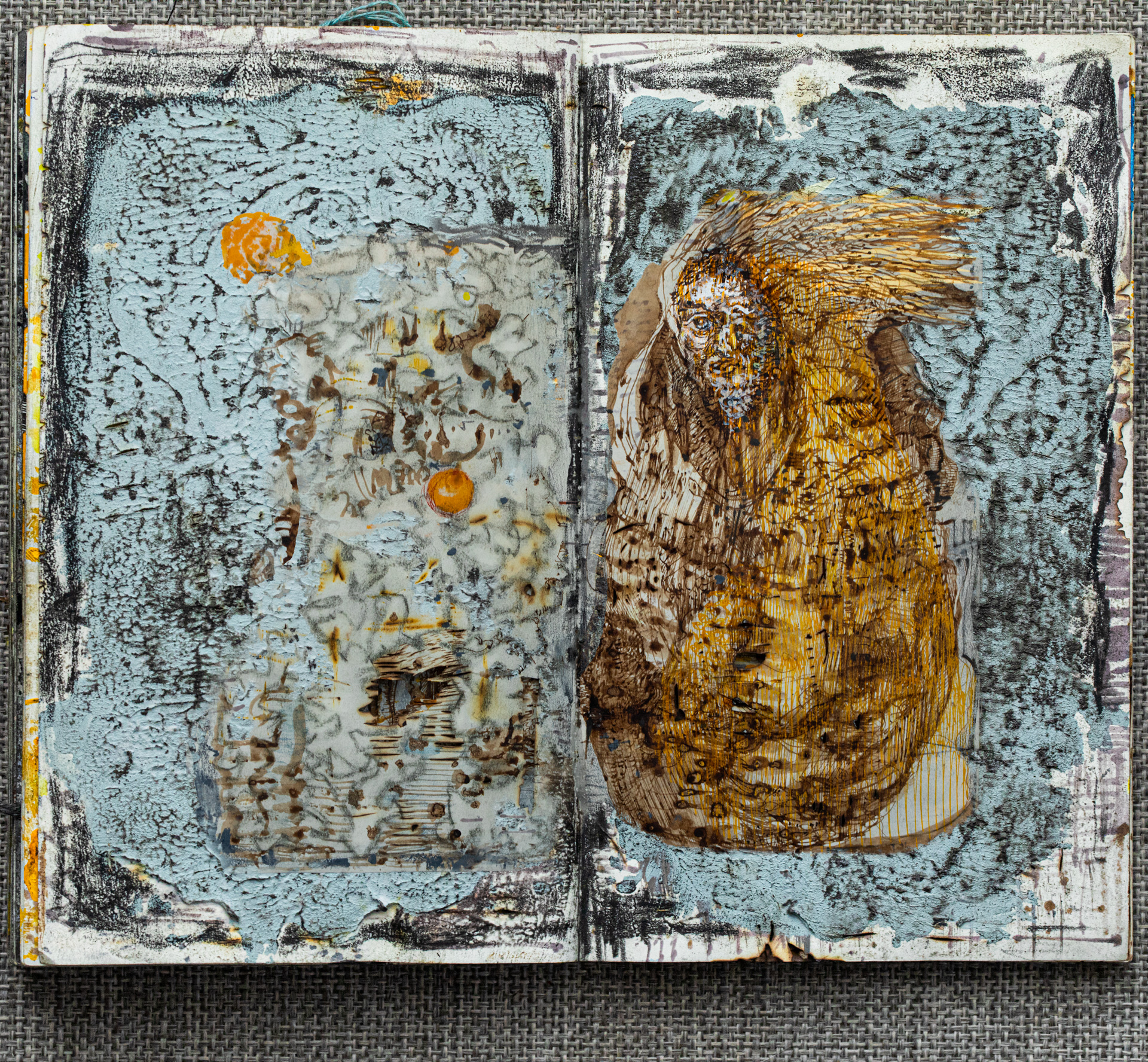

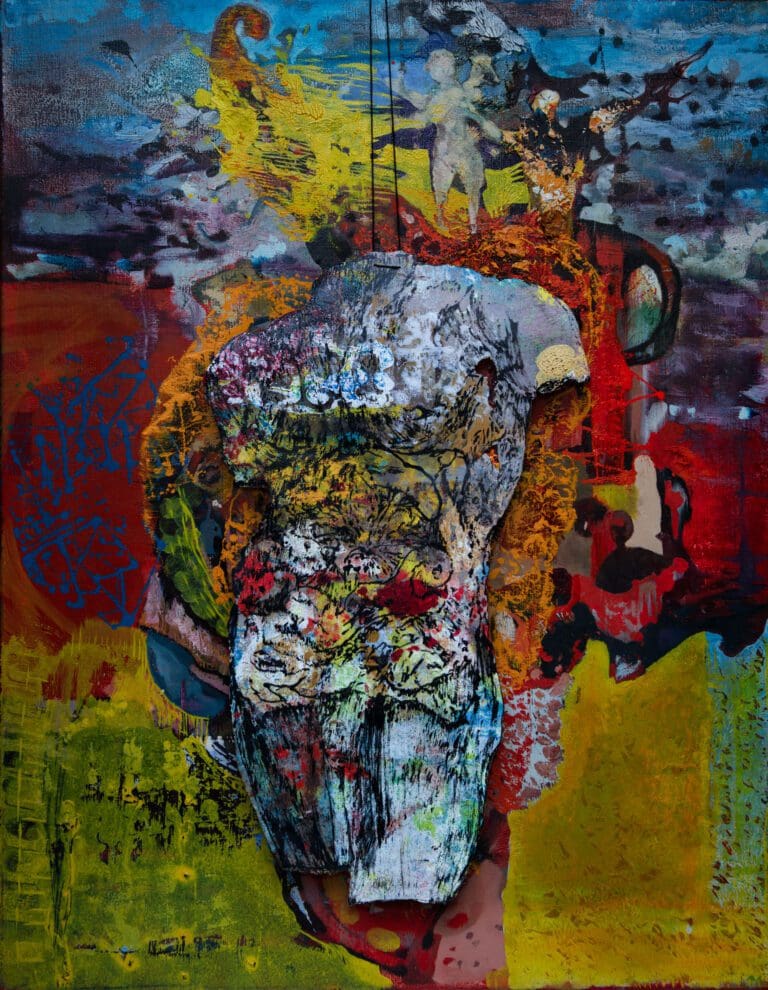

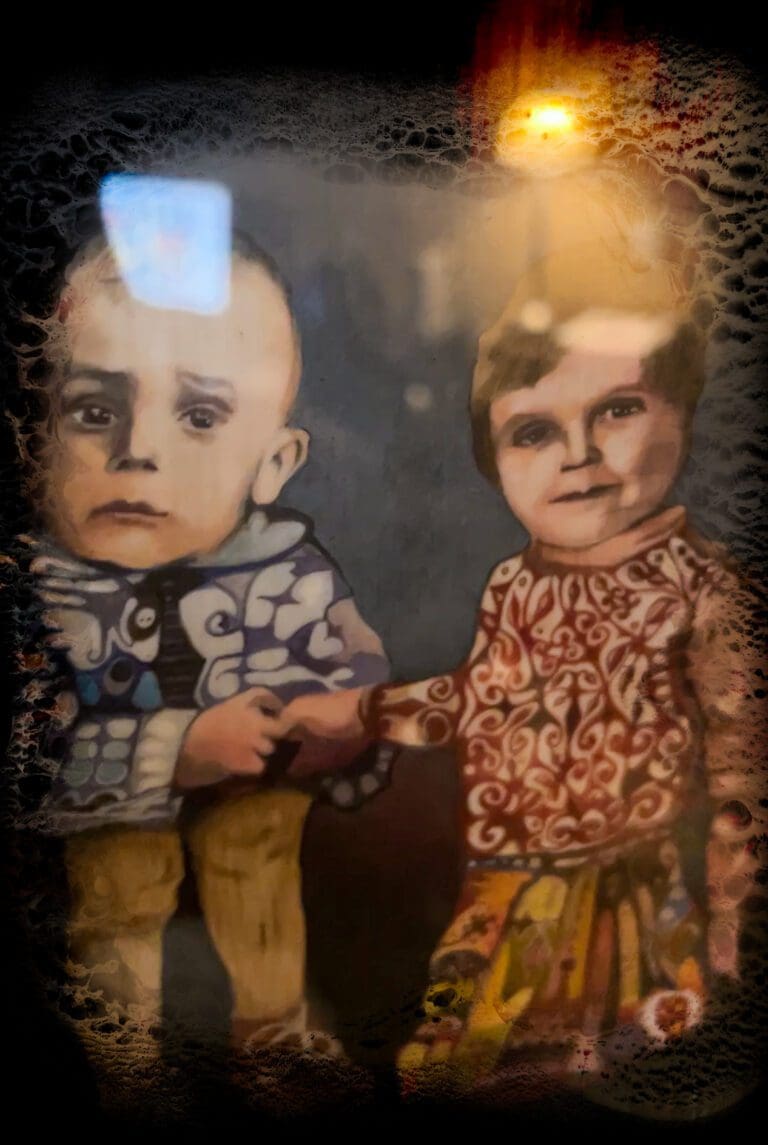

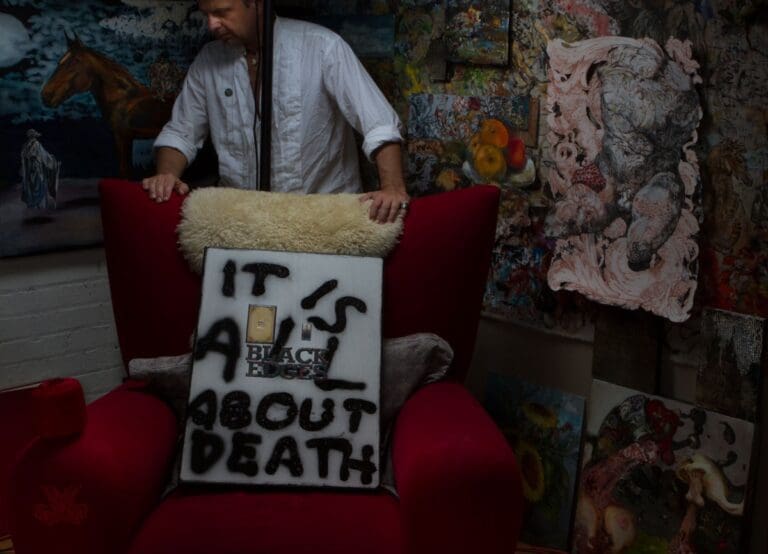

In our modern era, where the quest for the ideal often returns us to our imperfect, vulnerable selves, the charm of the torso remains undiminished. The battered, incomplete figures of stone no longer reflect an ideal form but rather a testament to resilience. They echo our human experience, where life often feels like a series of lost limbs and missing heads, yet the core stays strong. We are, at our essence, resilient and persistent, striving towards an elusive perfection.

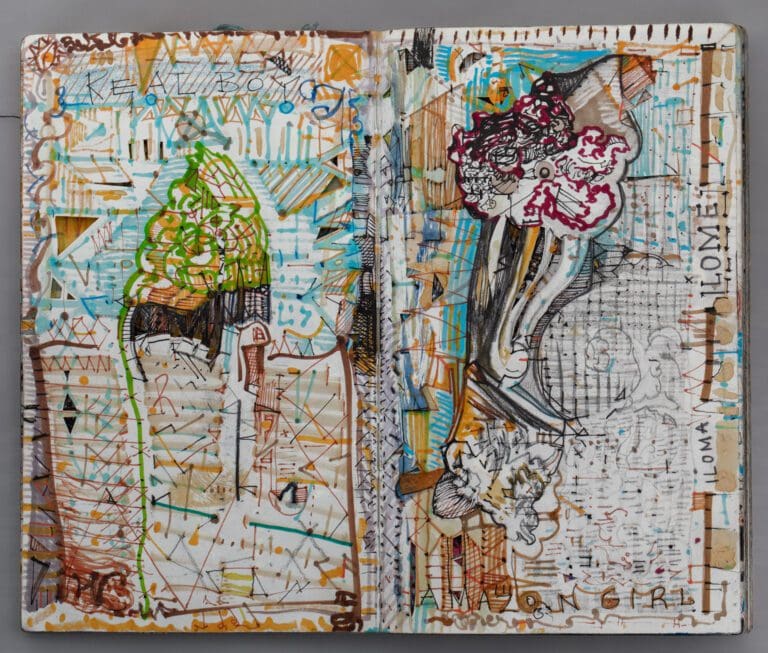

The torso, the core, the base, stands as a profound symbol, a canvas upon which the grand tapestry of human struggle, triumph, loss, and revival is painted. The power of the torso, of these beautiful broken forms, is that they are, in fact, whole. They’re symbolic of our human condition, our aspiration for perfection, and our acceptance of imperfection.

As we gaze upon these fragments, we see not what is missing, but what remains. The torso, then, is not a testament to the past alone, but a mirror of our present, a prophecy of our future. It’s an invitation to embrace the beauty of the broken, to find wholeness in incompleteness, and to continue our eternal dance with the ideal – one torso at a time.

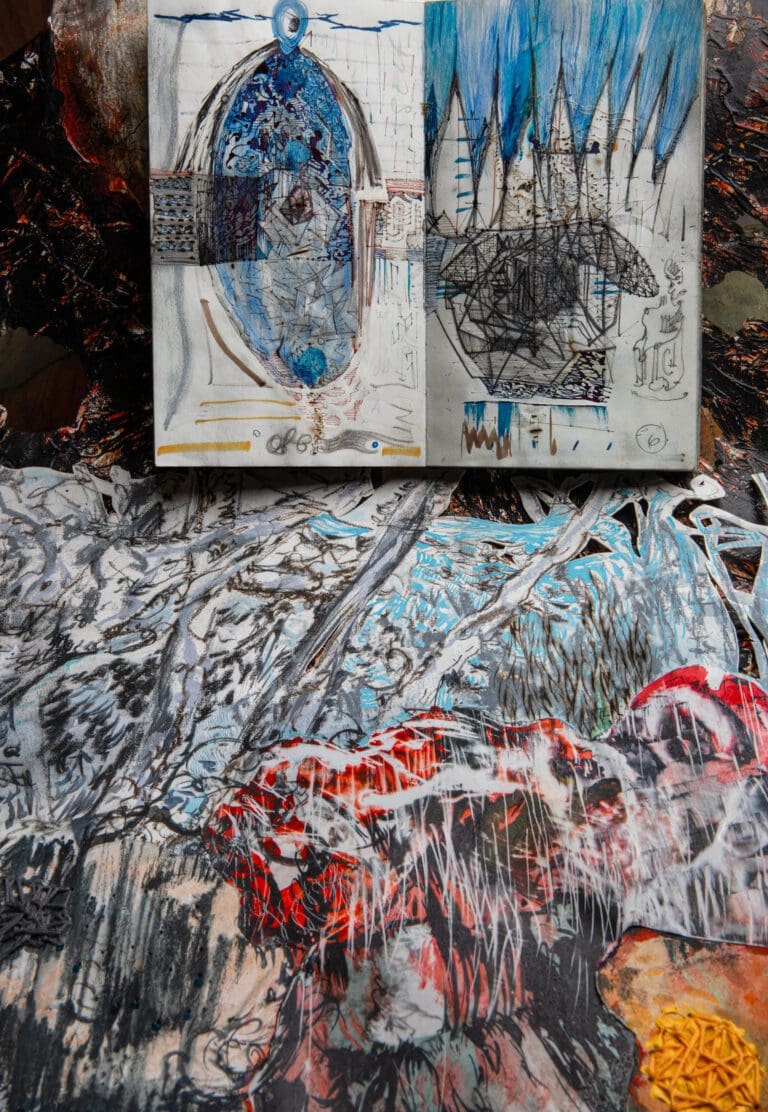

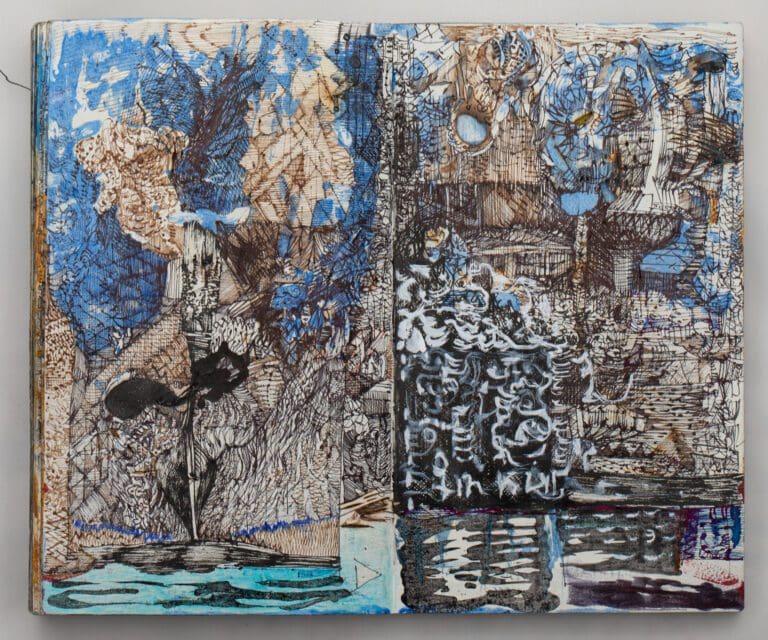

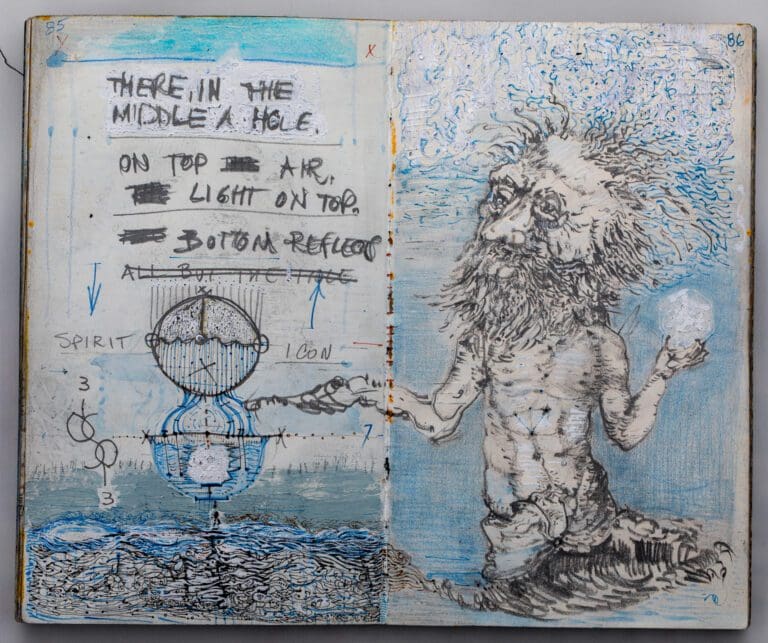

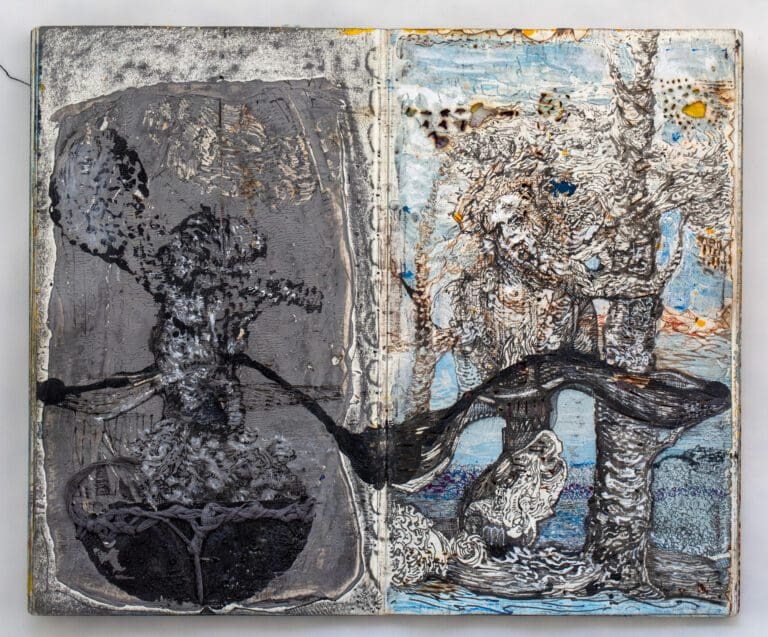

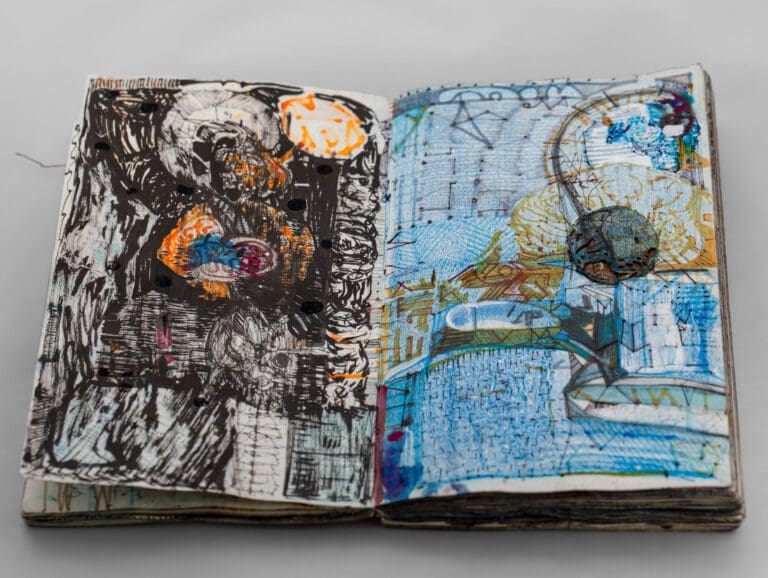

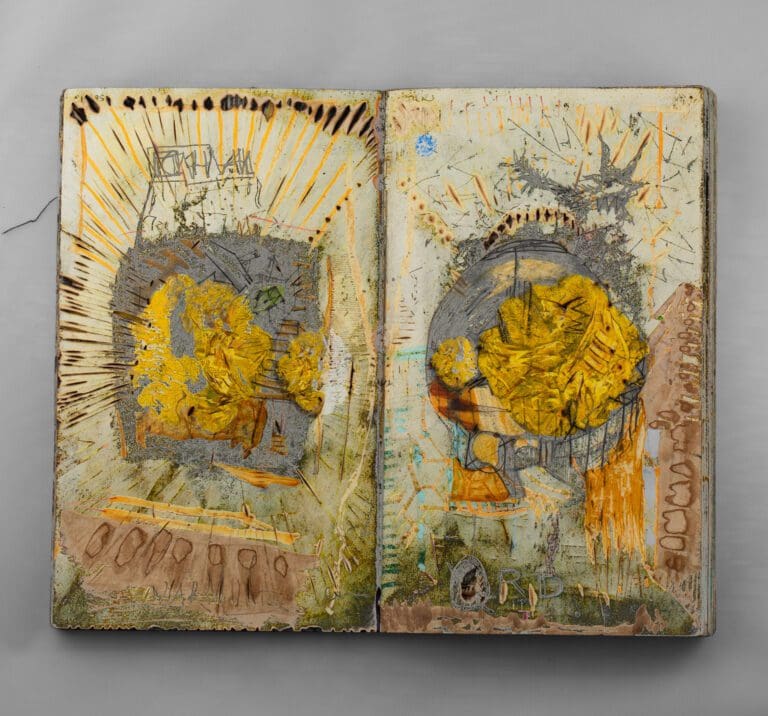

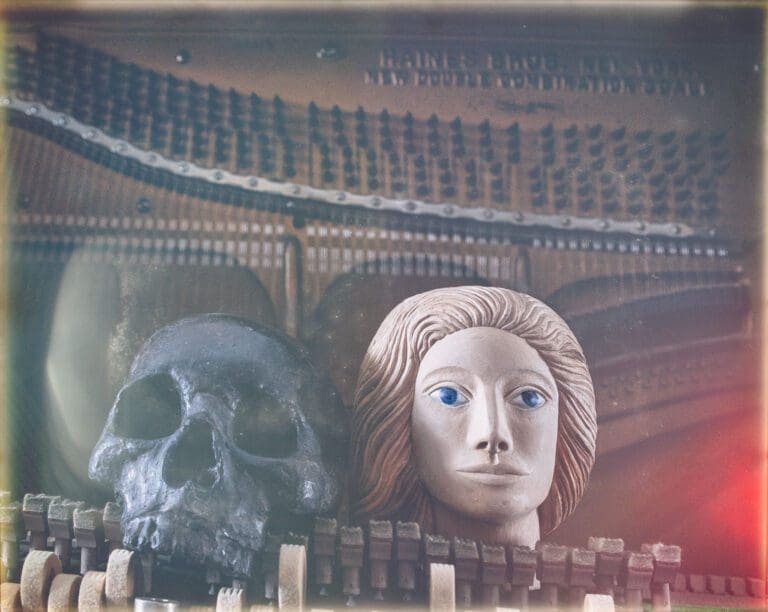

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”53″ exclusions=”552″ display=”pro_mosaic”]

The fascination with the nude

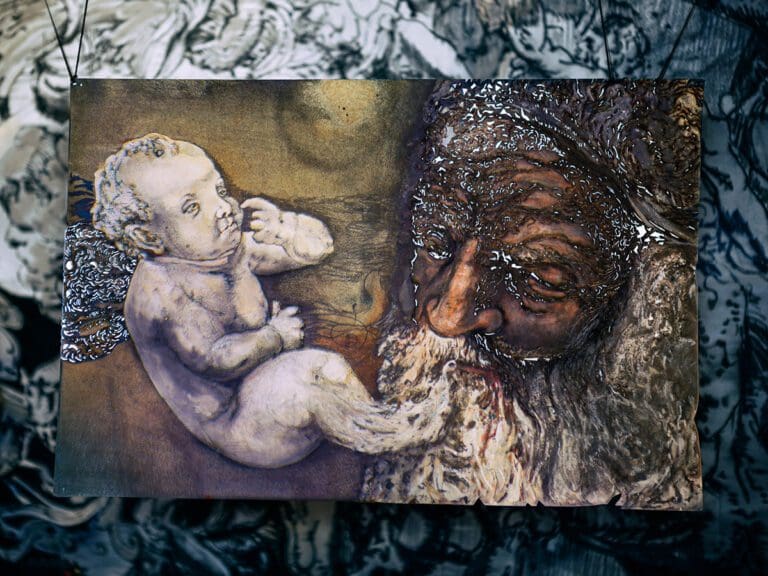

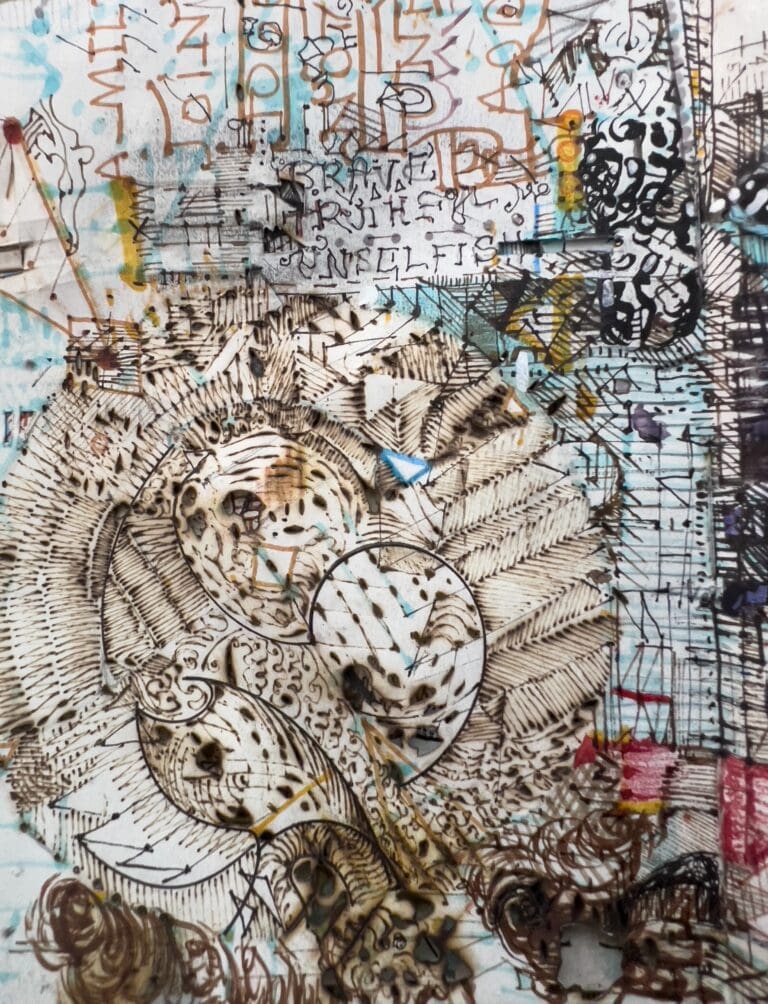

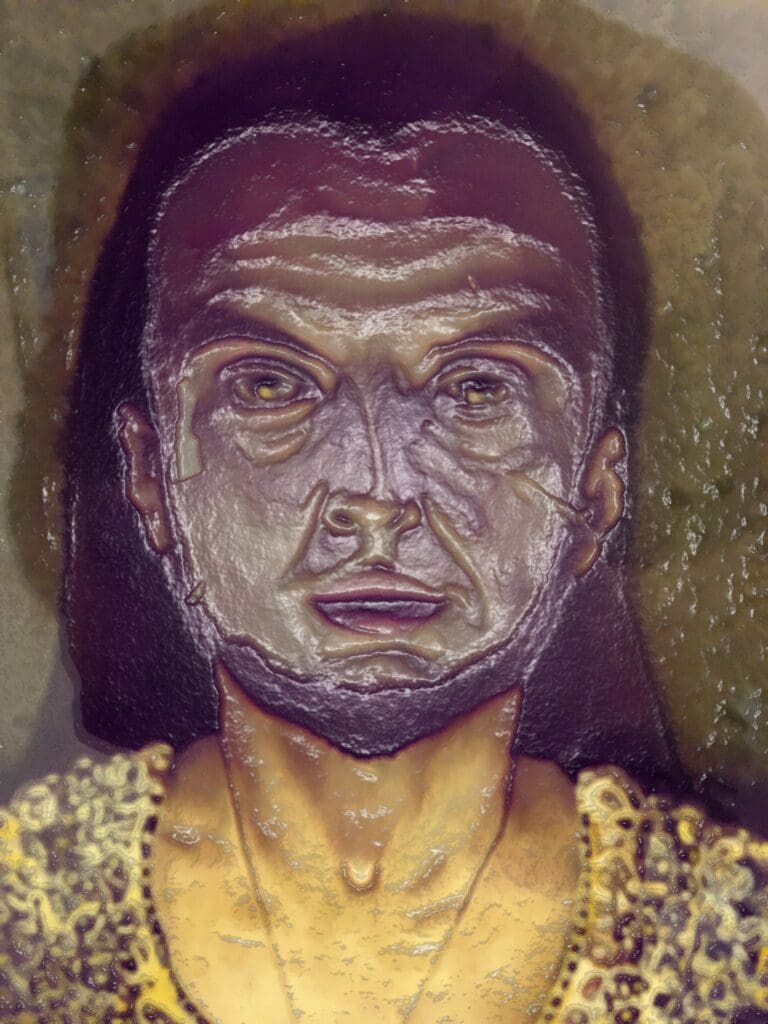

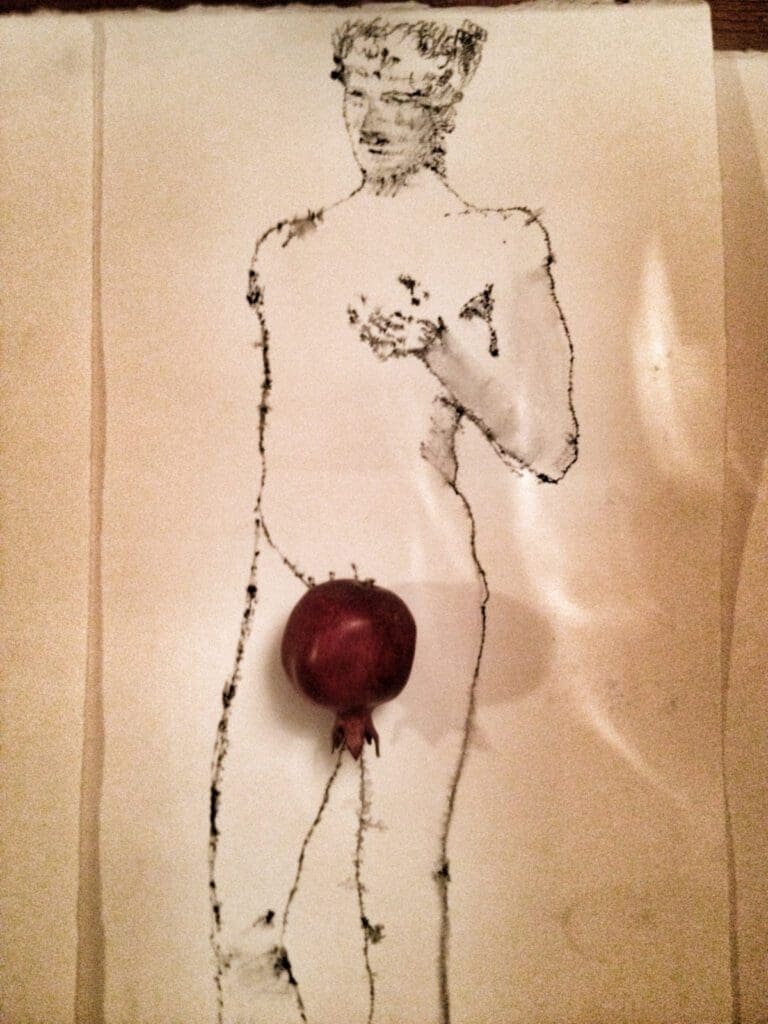

The fascination with the nude body, specifically the torso, through the lens of Carl Jung’s analytical psychology, brings forth the profound role of the ego and its interaction with our collective unconscious. According to Jung, the ego represents the conscious mind as it comprises the thoughts, memories, and emotions a person is aware of. It’s the narrator of our own stories, the “I” that one identifies with. Yet beneath this ego lies a vast reservoir of shared human experience – the collective unconscious, that speaks a universal language of symbols and archetypes.

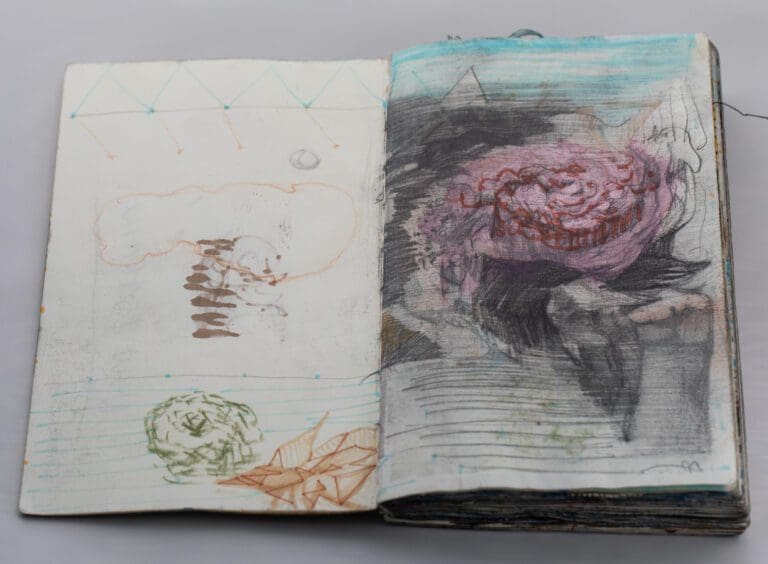

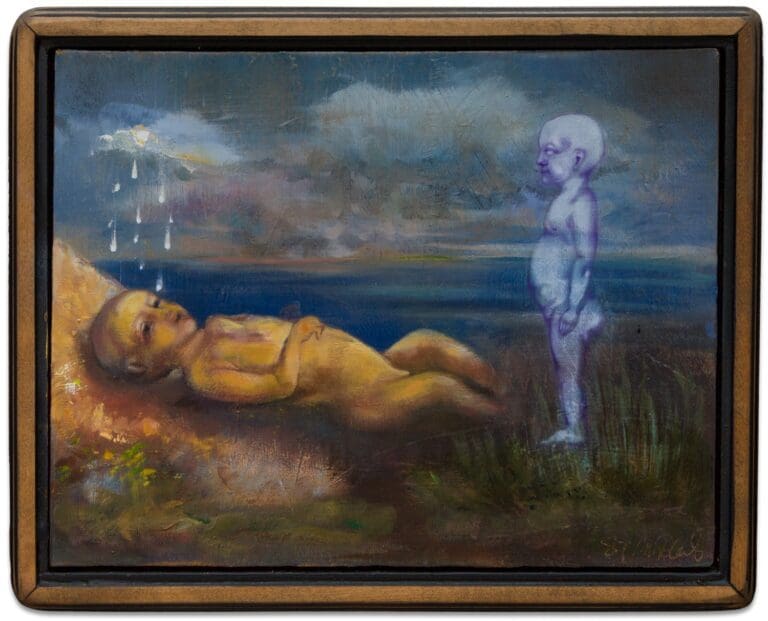

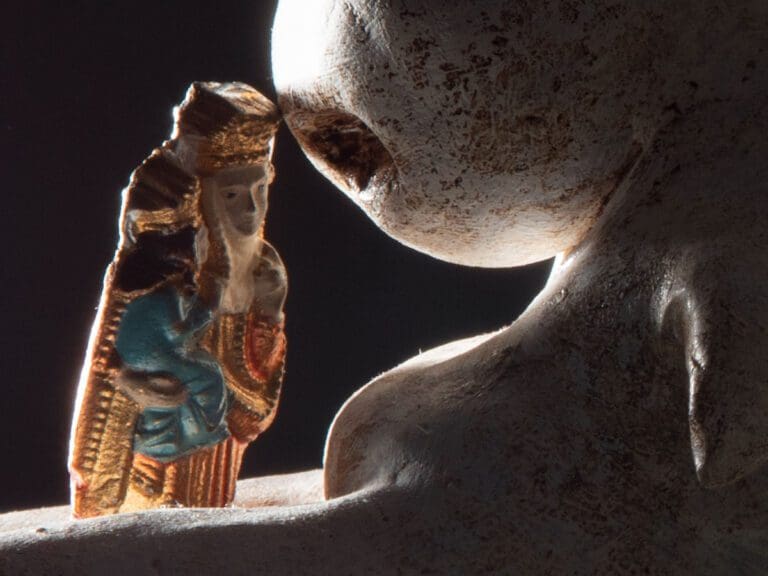

In the realm of art, the nude body serves as a symbol, a universal archetype, embodying themes that resonate with our collective unconscious. These archetypes are ancient, primal concepts that transcend culture and time, ingrained in the fabric of our shared human existence. The portrayal of the nude body, especially the torso, brings forth the archetype of the self, the integrated wholeness of our psyche.

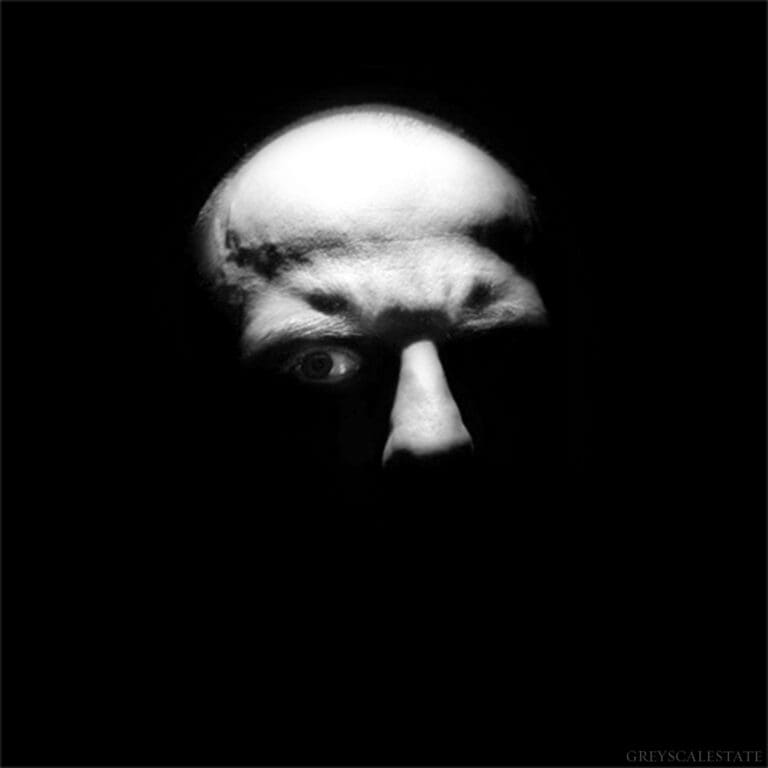

The torso, then, is not just a physical form but a metaphorical embodiment of our conscious and unconscious selves. Its dismembered state symbolizes the tension between the ego and the unconscious, the known and the unknown, the seen and the unseen. It’s a tangible reminder of our ongoing struggle to integrate our disparate selves into a cohesive whole.

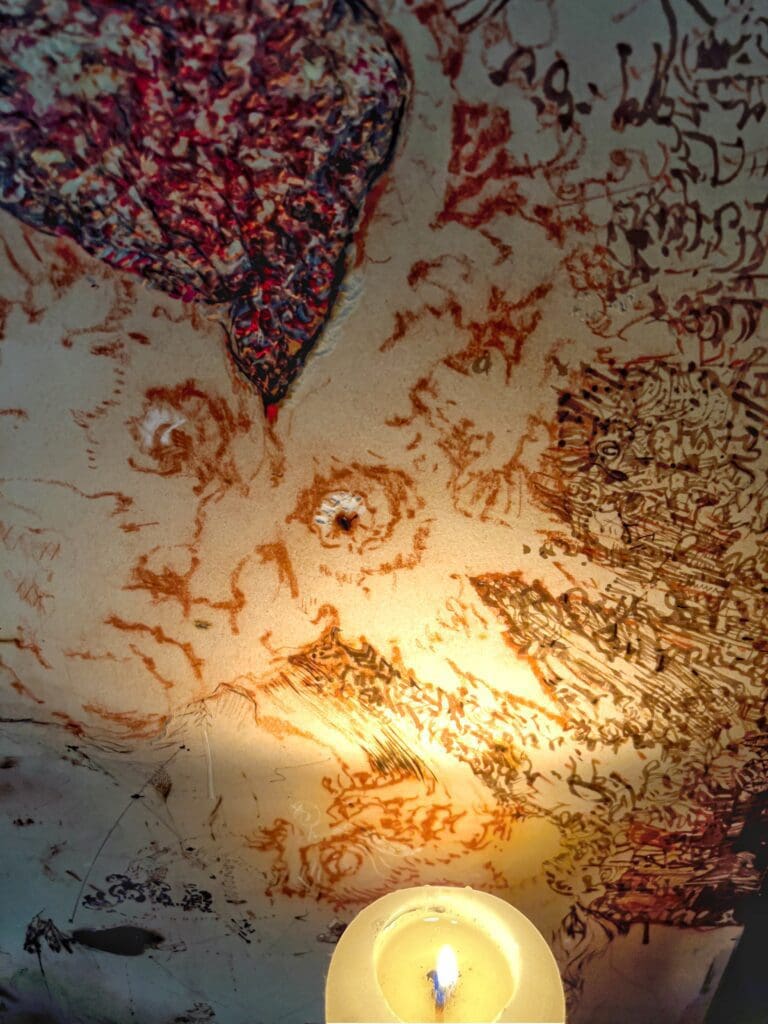

The fascination with the nude body, its idealization, and its enduring appeal, can thus be perceived as the ego’s attempt to dialogue with the unconscious. It’s an unconscious reaching out to the timeless archetypes of beauty, strength, vulnerability, and wholeness. The tactile marble form of the torso captures the intangible inner conflicts, desires, and quests of our psyches.

On one hand, the idealized nude body represents the ego’s aspiration for perfection, for unity and wholeness. Yet, its often fragmented form reminds us of our inherent human imperfections, our disconnection, our continuous journey toward self-integration. It’s a dance between the ego’s quest for individuality and its longing to reconnect with the collective unconscious, to return to the universal whole.

Moreover, the preservation of the genitals, as discussed earlier, brings to mind the Jungian concept of the anima (the feminine inner personality in the male unconscious) and animus (the masculine inner personality in the female unconscious). This aspect of the sculptures can be seen as the symbolic representation of these concepts, emphasizing the necessity of acknowledging and integrating these aspects for achieving wholeness.

So, as we stand before a fragmented statue, a solitary torso, we’re not merely observers but participants in a conversation that transcends time and culture. It’s a conversation between our ego and our unconscious, our individual and collective selves, our aspirations, and our realities.

The timeless allure of these sculptures, their seductive incompleteness, lies in their ability to resonate with our inner psyche, stirring the waters of our unconscious. They are, in essence, mirrors that reflect not just our physical forms, but our multifaceted selves – a testament to the enduring dance between our conscious and unconscious, our eternal quest for self-understanding and integration.